On Sept. 20, the Georgia State Election Board approved a rule requiring counties to hand-count all ballots cast in the November election. The new rule, passed by a 3-2 pro-Trump majority of the Board, is the latest in a string of rules that have caused widespread concern among election officials and democracy advocates leading up to the 2024 Presidential election. Fulton County, the state’s most populous county and the one with the largest Black population in Georgia, has been specifically targeted by the State Board, which has been accused of seeking to usurp the power of county authorities to govern its elections. The state board voted to select individuals to be part of the election monitoring team for the county, inspiring the county to sue the board.

While the Georgia State Board of Election seeks to gain control of Fulton County’s election process, it is not alone in its efforts more broadly. Republican-led state governments are increasingly taking over local governments, including local boards of elections, in majority-Democratic cities and counties.

In the U.S. federalist system, where the power to govern elections, school districts, police, and most court systems resides at the local level, the overthrow of local governments by hostile state actors is deeply undemocratic. Majority-Black communities have been experiencing these overthrows of their local governments since the post-Civil War period, and the most recent wave of these undemocratic overthrows could affect the outcome of the 2024 Presidential election.

Read More: Election Officials Warn Problems With U.S. Mail System Could Disrupt Voting

Following the Civil War, Southern states that were part of the Confederacy had to draft constitutions granting suffrage to Black men in order to rejoin the Union. The presence of federal troops in the South to enforce Reconstruction allowed for the expansion of democratic rights for African Americans. During Reconstruction, Black politicians were elected to thousands of seats throughout the South. Although several were elected to the U.S. Congress, the overwhelming majority were elected to state and local offices.

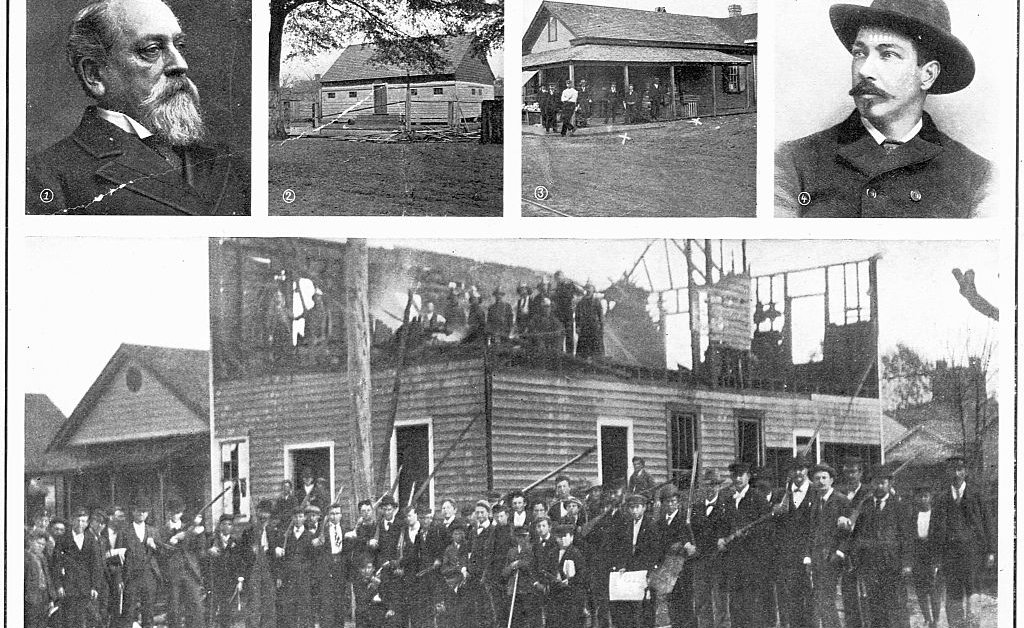

In response to the growth of Black political power in localities throughout the South, the Ku Klux Klan, working along with Southern Democrats—the party identified at the time as the “white man’s party”—organized campaigns of terror to intimidate Black voters. Terror campaigns began after the end of the Civil War and accelerated when the federal troops withdrew from the South in 1877. This resulted in the massacre of Black people in cities and towns where Black votes had led to the rise of Black elected officials and Republican control of state and local governments. Violent mobs overthrew Black and Republican political power in cities throughout the South, including in Wilmington, N.C., in 1898.

By the early 1900s, violent massacres were no longer needed to overthrow Black local governments in the South. As the federal government withdrew, Southern states rewrote their constitutions to include mechanisms for state oversight of local government functions like appointing officials to school boards and county boards of elections.

Most importantly, the new state constitutions implemented “Dillon’s Rule”—an 1870s doctrine named after an Iowa state judge named John Forrest Dillon—which stated that local governments only have the powers explicitly granted by their state governments. The power to suppress Black political power had shifted from the Klan to the courts, as states developed legal powers to control local governments. During the Jim Crow Era, state constitutions denied Black communities self-governance. Laws that disenfranchised voters legally sanctioned the violent overthrow of local governments.

The civil rights movement of the post-World War II era challenged legal segregation, including state laws preventing Black Americans from the political process. U.S. Supreme Court decisions like Brown v. Board of Education (1954) and federal legislation like the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Acts of 1965 yielded meaningful results in combating some of the more egregious forms of disenfranchisement and discrimination.

By the 1970s, Black communities across the country began to regain local political power by gaining majorities on local school boards and city councils, electing Black mayors, and gaining representation on county boards of elections in localities throughout the country.

However, as Black communities gained more political power, they also faced resistance from a resurgent conservative movement at the state level. The emergence of conservative organizations like the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), Heritage Foundation, and Cato Institute in the 1970s were instrumental in building a political agenda at the state level that began to undermine Black political power at the local level.

Education, particularly in Black-led cities, became a major target of such organizations and Republican state officials. In the 1980s, for example, state governments began to pass laws to take control of local school districts. The first of these state takeovers occurred in Northern cities like Newark and Detroit, where African Americans constituted the majority of the population. In these cities, Black communities were stripped of their ability to elect their school board members and govern their schools.

Read More: Why School Board Seats May Be the Hottest Races on Your Midterm Ballot

State takeovers of school boards expanded throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, including in Southern cities like New Orleans, as a result of state laws passed by Republican-led state governments that were ostensibly concerned about improving low performing school districts. While 30 years of evidence shows that schools do not improve following such takeovers, my research shows that the strongest predictor of a state takeover of a school district is not a district’s academic performance, but rather, whether they had a majority-Black student population and the city was led by Black political officials.

As a result of these takeovers, majority-Black local schools boards, which represented the foundation for the growth of Black political empowerment in the 1970s—much like they did in the 1870s—were abolished by state officials. In most instances, state officials created new state-appointed school boards and in some cases, particularly in rural communities in the South, school boards were abolished and not replaced at all.

Such takeovers have not been limited to local school districts. Republican-led state governments have taken over local police forces, courts, and financial management in cities with significant or majority Black populations. After the 2020 election, Republican state governments successfully passed laws that allow state officials to take over governance of local elections in Texas and Georgia. These laws have provided state authorities, like the Georgia State Election Board, the power to pass new rules that undermine local governance and authority.

While many Americans and observers of American politics are rightfully concerned about the upcoming election and the threat of another Jan. 6, American democracy is already under attack by hostile state actors undemocratically overthrowing local governments.

Domingo Morel is an associate professor of political science and public service at New York University and a Public Voices fellow with The OpEd Project. He is the author of Takeover: Race, Education, and American Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Made by History takes readers beyond the headlines with articles written and edited by professional historians. Learn more about Made by History at TIME here. Opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of TIME editors.