Last year, before a pandemic changed the world, surveys showed millennials and adult-age Generation Z respondents steadily developing a curiosity in cryptocurrencies if not buying into the bigger idea that the technology will transform money.

A Michelmores survey in the U.K., for example, found that 20% of affluent millennials – the cohort born between 1980 and 1996 – invested in cryptocurrencies, compared with just 3% for the general population. Meanwhile, an online Harris/Blockchain Capital poll found 60% of people aged 18-34, a demographic covering six years of Gen Zers and 10 of millennials, were “somewhat familiar” with bitcoin, compared with 43% overall.

But the results also revealed that, in the U.S. and U.K. at least, this generational pairing still holds much more faith in traditional investments such as stocks and bonds. The data suggest a cohort of crypto dabblers, not outright converts.

You’re reading Money Reimagined, a weekly look at the technological, economic and social events and trends that are redefining our relationship with money and transforming the global financial system. You can subscribe to this and all of CryptoX’s newsletters here.

What will take this all-important group of digital natives to the next level? How might they see crypto and blockchain technology as diehard believers do, as the driver of an entirely new paradigm for money, investing and wealth accumulation?

Perhaps COVID-19 is the catalyst.

Consider the pandemic’s global economic fallout: the equivalent of 400 million full-time jobs in lost work hours, a mountain of deferred bankruptcies, government debt levels above or projected to exceed 100% of GDP. Just as the Great Depression shaped economic decision making for decades, the shock of COVID-19 will be felt for a very long time.

The future decisions that matter will be those of Gen Zers and millennials, who together account for more than 60% of the global population. I see their decisions leading them to bitcoin.

Attitude shock

I have two Gen Z daughters. One is entering her second year of college just as she ended her first: homebound, learning virtually. The other is starting her critical junior year of high school in the same situation. It’s hard not to feel they are being denied some key rites of passage in their journey into adulthood.

Yet, they are among the luckiest. A Pew Research survey early in the crisis found that half of adult-age Gen Zers (ages 18 to 23) said they or someone else in their household had lost a job or suffered a pay cut because of the pandemic.

Meanwhile, many millennials, the youngest of whom are 24, are facing life-defining decisions about marriage, children, home-buying, career paths and long-term investment strategies in a uncertain economic environment. COVID-19 has barged into this defining period of their lives. It seems inevitable it will reset their expectations of the future.

Already, per a Harris Poll study for Edward Jones and Age Wave, about a third of both Gen Z and millennial respondents foresee an “extremely or very negative impact” on their personal financial security due to COVID-19. That compares with 24% of Generation X, 16% of baby boomers and 6% of the silent generation.

Given that a currency’s worth as a store of value is dictated by how users view its value over time, deteriorating expectations about future earning potential will inevitably shape how millennials’ and Gen Zers’ think about the money they use.

Even before this tragedy, these two generations were primed for a major attitude shift toward digital money. Growing up with the internet, they’re more inclined to its DIY ethos and notions of autonomy, as the lines between user and publisher blurred online and gave everyone the sense that they had their “own voice.” It might not be that much of a leap for them to embrace the “be your own bank” mindset of bitcoiners.

What to do when yield Is zero

Expectations and attitude shifts provide a potential cultural impetus for these groups to change how they think about money. Now there’s also a financial motive, as stocks and bonds, pumped by unprecedented central bank quantitative easing, are delivering stubbornly low yields – their earnings as a percentage of price.

With central bank rates anchored close to zero in dozens of countries, checking and savings accounts are paying a pittance and government and corporate bond yields have plunged, in some cases into negative territory. Meanwhile, with companies’ profitability whacked by the crisis, stock dividends have suffered their biggest quarterly drop in 11 years.

The two-decade fall in bond yields that got us here was a positive development for those who owned them because a decline entails a rise in price delivering a capital gain. Very few of those owners were millennials and even fewer, if any, Gen Zers. Rather, the benefits accrued to older Generation Xers and baby boomers.

Now, yields can go no lower. The younger generations can expect neither interest rate earnings or capital upside, right when they are primed to invest in these markets for the next half century.

This mightn’t matter if stocks were destined to rise. After all, low bond yields make stocks look attractive by comparison.

But it’s impossible now to argue that stocks aren’t in a bubble inflated by massive amounts of central bank intervention. Valuation measures are screaming “overbought.” In addition to plunging dividend yields, the S&P 500 median price-earnings ratio has never been higher.

If this is the top, millennials and Gen Zers have nothing left to buy. The same goes for home prices, now completely out of their range and with future gains curtailed by the lower-bound limits on near-rock-bottom mortgage rates.

No infinite treadmill

If the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan could keep up the trillions of dollars of new money creation ad infinitum, maybe this treadmill could go on forever. P/E ratios would go into the stratosphere and millennials and Gen Zers would just hitch themselves to the ongoing stock market inflation, passing the risk onto whatever generation is coming up behind them.

At a minimum that would require a continuation of the best-of-both-worlds conditions that have sustained stocks for almost three decades: low inflation and solid economic growth.

COVID-19 – and the policy response it is encouraging – will, I believe, render both impossible. The handling of the pandemic has severely hurt global confidence in the U.S. government, while the Fed’s monetary expansion (essentially confirmed by a policy shift announced Thursday), has undermined confidence in the dollar, generating inflation. Meanwhile, the blow to growth from the lockdown and future constraints on travel and work, coupled with ballooning debt levels that must be reined in, will make it much harder for businesses and governments to fund themselves.

In short, inflation will outstrip both bond yields and corporate earnings for the foreseeable future, which means a loss in real terms. That, clearly, is bad news for millennials and Gen Zers who are looking for a reliable way to accumulate wealth for the future.

More fundamentally, that loss-making equation will challenge their very faith in the fiat currencies in which they currently save.

Will that lead them to store value in bitcoin, which earns no nominal interest on its own? Maybe.

If younger generations can accept bitcoin’s promise of digital scarcity and censorship resistance and value its protection against currency debasement, political uncertainty, confiscation and economic dependency, it will look increasingly valuable relative to the low yields on overvalued fiat-based assets.

Ultimately, it’s the millennials’ and Gen Zers’ prerogative. Do they throw their lot in with the old monetary system of the boomers and Gen Xers, or build themselves a new one that serves their interests?

50 Years of Fiat Yields

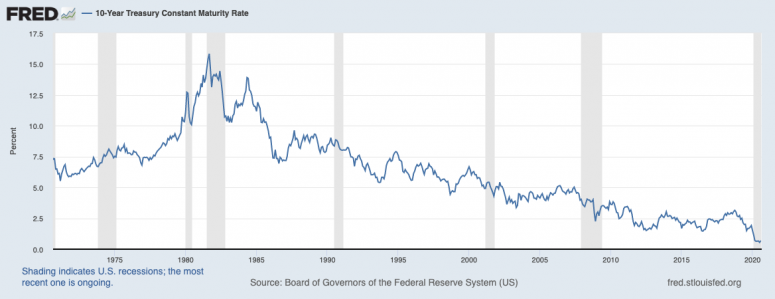

Doing research for this week’s column, I took a look at a long-cycle trend for 10-year bond yields. Fifty years seemed like the right time frame, given that next year around this time the world will mark the half-century anniversary of the “Nixon Shock,” the moment when President Richard Nixon removed the dollar from its peg to gold and single-handedly created the fiat money era.

What we see in the first 10 years of the chart below (courtesy of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’s fabulous FRED service) is the initial impact of that dramatic change. Coupled with the OPEC oil embargo, the arrival of floating currencies triggered a frightening surge in inflation, which ultimately forced Fed Chairman Paul Volcker to jack up interest rates to nose-bleed levels. That meant the yield on the 10-year Treasury note also soared as the cost of borrowing money climbed. Volcker’s painful move triggered two recessions in quick succession – recessions are marked in gray on FRED charts – in the early 1980s. But once he’d broken the back of inflation and established a sense of solid trust in central bank independence as a principle, a period known as the “Great Moderation” began. Inflation fell and yields came down. And it didn’t stop for 40 years.

For a long time, this was, quite reasonably, seen as a good thing. Killing inflation and lowering borrowing costs established the conditions for a long period of U.S. economic growth. It paid for the United States’ victory in the Cold War, which in turn paved the way for a new American-modeled version of global capitalism, which poured money into emerging markets.

But the enthusiasm it generated also bred a more pernicious boom-bust cycle as a series of crises, especially in those emerging markets, demonstrated the vulnerability of global investors to credit risks in an increasingly interconnected world. In the 1990s, that ushered in an era in which central banks – especially the Fed – were seen not only as managers of price conditions but as market backstops in times of uncertainty and panic. (Background reading: “The Greenspan Put.”) It reached a crescendo with the global financial crisis of 2008 and its aftermath. That’s when the Fed drove rates down to their final bottom limit, the “zero bound,” but still saw a need to stimulate a shell-shocked economy, creating trillions of dollars in bank reserves via an unprecedented “quantitative easing” policy.

Now, amid a new crisis, we’re back there again, with the Fed issuing even greater amounts of new money, propping up the stock market, and wondering what more it can do to stop things from falling apart. Why the concern? Why not just let the market retrace? Because it could trigger a reversal in that 40-year rally in bond prices – the flipside of the slide in yields – a situation that some see as the biggest, most dangerous bubble in the world. Those U.S. government bonds are held by all the world’s central banks and commercial banks in huge quantities, where they provide sought-after collateral for all sorts of secondary loans. If that house of cards was to fall, it might have a bigger impact than even the Nixon Shock.

Global town hall

BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU WISH FOR. During one of the finance industry’s most heavily anticipated speeches, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell dropped news of a significant policy shift. From now on, the Fed will not just target inflation around 2% but will do so on an average basis over longer periods. In other words, to compensate for periods in which inflation is too low, it will tolerate a rate above 2% for a longer period. While Powell was clear that the Fed can dial up monetary tightening at any time, that it will prioritize employment goals over those of inflation, and that it’s not bound to a fixed time frame, the key question here is what this new message does to people’s inflation expectations. Can the Fed manage them?

These kinds of announcements are often designed to manage expectations and demonstrate the Fed’s commitment to its objectives. The policy itself is not the only tool. Announcing the policy itself signals intent – like saying, “See, your fears that we are going to suddenly withdraw monetary easing are unwarranted: We’re so committed to doing all we can to keep borrowing rates low that we’re pledging to let inflation go over our target for longer.”

But what if the messaging is too clear? What if the market reads this as the “Fed will create inflation, no matter what?” Inflation is a function of inflation expectations and of market confidence that central banks will protect the value of the currency. In an environment where confidence in government is waning, where gold is at record highs, and stocks are overvalued, will the Fed’s explicit promise to allow some degree of excess inflation inadvertently create a worse problem once the economy recovers? That’s the trillion-dollar question.

CONFUSED ABOUT CRYPTO? ASK THE IMF. This could have been cringey. The International Monetary Fund, a bastion of bureaucrats synonymous with the old-order fiat financial system, published an explainer video on cryptocurrencies. But in many respects, the two-minute piece, featuring a woman narrator walking through a field of animation talking about the problem of payment intermediaries and the “science of cryptography,” was a masterful effort.

To be sure, it didn’t dive into proof-of-work consensus mechanisms or protocol-based monetary policy, and it inevitably attracted mockery from maximalists who complained that it glossed over their favorite bitcoin features such as digital scarcity and censorship resistance. But as something to share with newbies, to get their heads in a place to start going down the rabbit hole, this is a surprisingly useful addition to the Crypto 101 resource list. We really shouldn’t be so surprised. The IMF has had an energetic and intelligent team of economists digging into cryptocurrencies and central bank digital currencies for about five years.

OMG OMFIF! The Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a think tank commonly referred to as OMFIF, includes among its membership many central banks, sovereign wealth funds and multilateral institutions (as well as private sector entities such as investment firms and banks), which gain access to new ideas around monetary policy, including on digital currencies.

So, it’s striking that OMFIF’s deputy chairman penned a lead article for its online publication with the title “Dollar Supremacy at Risk.” Philip Middleton’s argument will be familiar to readers of this column in that it ties the rise of digital currencies to a challenging macro environment marked by financial stress and international tensions. He writes that a “perfect storm produced by the convergence of geopolitics, technology, social change and the [COVID-19] crisis could bring about a profound shift” to knock the dollar off its perch as the world’s reserve currency.

Talking about this kind of thing was unimaginable in official circles a year or so ago. Also striking: Middleton’s suggestion that, in order to get ahead of this risk, the U.S. “might do worse than commission a Silicon Valley giant to offer a digital dollar to its billions of users worldwide.” A much friendlier message than a certain Silicon Valley giant received from central bankers a year ago when it proposed rolling out a basket-based digital currency to its billions of users worldwide.

Relevant reads

What Ethereum’s Fees Mean for Its Future. CryptoX columnist Nic Carter brings a new argument to an old debate. The high fees the DeFi mania have brought to a now overburdened Ethereum network prove that public blockchains’ place in the world lies in acting as financial infrastructure, as the settlement layers for large-scale financial transactions; transactions are simply too expensive to play an effective role enabling non-financial data transfers or small, “cup of coffee” transactions. Carter says that Bitcoin Core advocates resolved themselves to this some time ago during the bitterly fought block-size debate with Bitcoin Cash advocates, but only now, amid the DeFi boom, are many in the Ethereum community doing similarly.

No Collateral Required: How Aave Brought Unsecured Borrowing to DeFi. The early phase of DeFi depended on taking cryptocurrency holdings and locking them in over-collateralized smart contracts to unlock automated credit lines that manage to keep asset values stable without the intervention of an intermediary. But what if the borrower doesn’t have collateral? Brady Dale explains how the Aava protocol has built a DeFi system that uses a delegated collateral system to allow people to borrow without putting down assets as security. Unsecured credit: yet another way in which DeFi innovators are trying to replicate traditional finance in a decentralized setting.

Boston Fed Is Looking at ’30 to 40′ Blockchain Networks for Digital Dollar Experiments. The Boston Fed, which only recently went public with the fact that it has been experimenting with a digital dollar solution, is casting a very wide net to figure out the best approach. And it’s not just thinking about an in-house solution. Nikhilesh De reports.

DeFi Is Just Like the ICO Boom and Regulators Are Circling. Lawyers Donna Redel and Olta Andoni offer a friendly warning to DeFi entrepreneurs in this OpEd. Citing clear similarities with the initial coin offering boom of 2017, Redel and Andoni say that the token issuance activity that DeFi is spawning will inevitably attract regulatory attention and that it might not end well for them. They suggest working with regulators to develop “sandbox” experimental arrangements that allow for some innovative free rein but also give government agencies like the Securities and Exchange Commission an opportunity to build some certainty and order to this Wild West sector.