All of a sudden, it seems that everybody in the Ethereum ecosystem is talking about native rollups, with Ethereum Foundation researcher Justin Drake saying that everyone he’s spoken to about the proposal has been immediately supportive.

Optimism, Base, and half a dozen other L2s have expressed a desire to incorporate the tech into their platforms — and some also want to also become “based rollups” for good measure.

But with Drake’s January post on EthResearch aimed at a technical audience and most other explainers using the arcane terminology of blockchain devs, many ordinary Ethereum supporters may be left with little idea what native rollups are or how they work.

So, we’ve roped in experts from the 2077 Collective and the Ethereum Foundation to help explain it in plain English.

What is a native rollup?

The TLDR is that native rollups make L2s as secure and trustless as Ethereum itself by getting the base layer to take care of all the stuff that currently requires a complicated and difficult Zero Knowledge (ZK), or fraud, proof system on every L2.

From a user’s perspective, you could feel as safe and secure keeping your $10 million in life savings on a native rollup as you would storing it on Ethereum itself.

“Native rollups seem like a no-brainer for rollups. They are so much simpler and much more secure,” explains Ethereum Foundation researcher Ladislaus.

“They can inherit L1 security with just a few lines of code by calling the precompile in the future.”

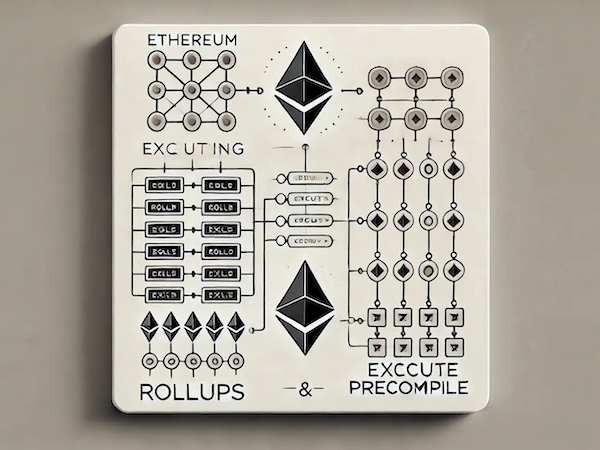

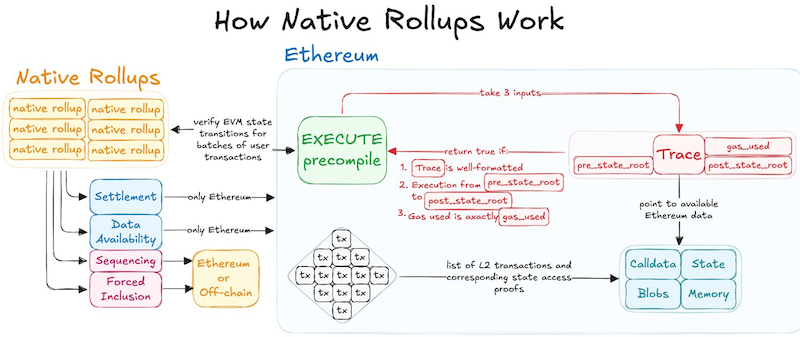

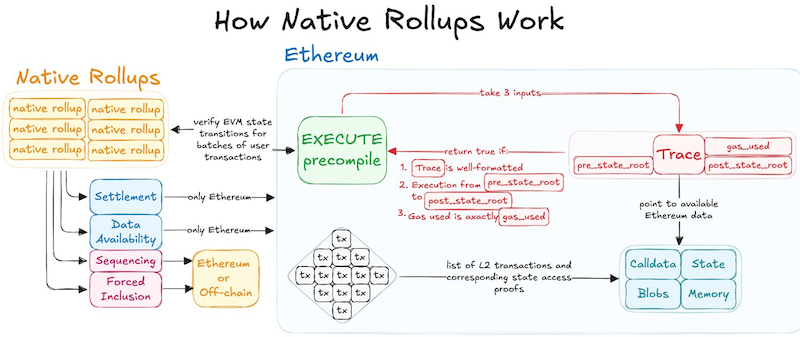

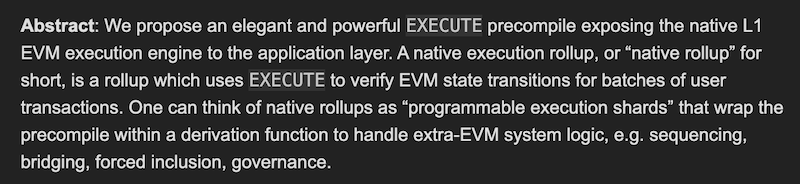

“Precompile” refers to a special type of contract hardcoded into the Ethereum protocol that extends the Ethereum Virtual Machine’s (EVM’s) capabilities. Drake’s proposal is for “an elegant and powerful execute precompile” that turns the native rollups into “programmable execution shards.”

So you can think of it as sort of a reboot of the old Eth 2.0 sharding plan.

How do native rollups work?

Basically, they’re an overhaul of the way proofs work on L2s. These are little cryptographical snapshots that record the state of who owns what on the rollups that are periodically written to Ethereum. By recording the state of L2s on the Ethereum blockchain, rollups benefit from Ethereum’s massive decentralized network, and users are able to permissionlessly withdraw their funds from rollups if required and force through transactions censored by the sequencer.

At present, Ethereum Virtual Machine-compatible optimistic rollups essentially just assume everything that happened was correct (hence the name) and write that to Ethereum. Then there’s a seven-day period during which a few select actors can challenge anything dodgy with a “fraud proof” before assets can be withdrawn to Ethereum.

EVM-compatible ZK-rollups like Linea, however, use cryptographic proofs that show beyond a shadow of a doubt that the relevant computation was performed on the rollup, which allows for much faster withdrawals to the L1.

Also read: Pectra hard fork explained — Will it get Ethereum back on track?

The native rollup proposal would mean the L2s would not need to establish the same sorts of elaborate proof systems and security councils as they do now. Instead, they provide the Ethereum base layer with a list of transactions called a “trace.”

The execute precompile then uses Ethereum’s execution engine to re-execute the computation and verify the state transitions, which is just a fancy way of saying that it makes sure that whatever just happened on the rollup was correct.

Later versions will see ZK-proofs incorporated, which is when native rollups will shine.

What are the benefits of native rollups?

The major benefits are that the rollups won’t need to build difficult and complex proof systems or rely on security councils or multisigs, allowing a small trusted group to step in when things go wrong or if the proofs are buggy.

“Native rollups don’t risk being drained due to a problem with the proof system and can safely get rid of security councils, improving their decentralization,” says Alex Hook, a researcher at 2077 and Untronfi CEO.

And for users, Hook says, “Their funds on a native rollup are as secure as Ethereum with no trust assumptions added.”

The problems with native rollups

For the L1, Hook says, native rollups bring “fully secure and decentralized scaling at the cost of significantly increased protocol complexity.”

Another issue is that using Ethereum nodes to re-execute the transactions to verify they’re all kosher would be very slow and seems to contradict the whole point of rollups, which is to move execution off of the achingly slow Ethereum base layer.

While the execute precompile is designed to be slightly more efficient than full re-execution, Drake says the first version should just be seen as a “stepping stone” along the road.

Ladislaus notes it may end up being well suited to optimistic rollups.

“This is because optimistic rollups only need to call the precompile to settle a fraud-proof challenge. So the verification of that challenge would actually be the only (tiny) overhead for L1 validators to take care of,” he says.

The longer-term plan is to get Ethereum block builders to generate ZK-proofs and then get the nodes to verify them, which eliminates the need to re-execute everything.

The longer, long-term plan is “ideally, proving a ZK-EVM block for Ethereum at some point can be done on a Macbook Pro,” Ladislaus says.

At present ZK-proofs aren’t fast enough to be incorporated. ZK-proofs are also expensive, which is why ZK-rollups haven’t really taken off yet.

One solution to make the system more efficient would be to use a recursive proof instead — which is a proof of a bunch of other proofs and is similar to batching and compressing proofs to make them more efficient.

Teething problems and potential solutions

As things currently stand, each rollup has mucked around with their version of the EVM, and making the Ethereum execution engine work with all these modded systems would be difficult. Standards will probably need to be established before rollups upgrade themselves to native rollups to make sure their targeted optimizations are compatible. Or they might just choose to use an exact copy of the EVM.

This is a feature and not a bug, though, as the EVM-compatible rollups currently have to keep upgrading themselves to keep up with the regular hard forks of Ethereum. This is a security risk and can introduce bugs. However, native rollups could update automatically with L1 hardforks.

Hook says this would make devs’ lives easier as there would be “less dev friction.”

“Today, most L2s detach from the L1 spec in some way or form, and devs always have to keep these differences in mind,” he says.

Potential data availability issues for native rollups

As with everything on the Ethereum roadmap, data availability looms as an issue.

Native rollups need to publish state witnesses, which will fill up a lot of data blobs, and capacity is already constrained. That said, blobs are doubling in the next fork and then increasing by 2x to 4x in the Fusaka fork, which is being fast-tracked this year.

Ladislaus notes that native rollups must either be rollups (meaning they use Ethereum data availability) or optimums (optimistic rollups that use alternative DA like Celestia or EigenDA). He said it is not possible to have native validiums, which is when a ZK-rollup uses altDA “which may increase demand for Ethereum DA.”

Read also

What is the timeline for native rollups to be implemented?

It’s still early days for native rollups, with Drake’s post on EthResearch.ch going up in January, and two community calls have been held so far.

But support for the idea is growing, and half a dozen L2s spoke in favor during January’s sequencing call.

“Optimism is willing to support based sequencing and native execution. It’s wartime,” co-founder Ben Jones said.

“We need to scale and connect the Ethereum ecosystem and based sequencing and native execution feel like the tools to do it,” said Jesse Pollak from Base.

Ladislaus says the eager interest in the proposal from rollup founders “demonstrates a certain urgency and ‘product-market-fit’ for such services offered by Ethereum.”

Even so, the proposal is unlikely to be included in either the Pectra hard fork (on testnet now) or Fusaka later this year (which will be hyper-focused on scaling blobs).

That means it will have to wait at least until “Glamsterdam” — which is the early name for the fork coming after Fusaka. Drake suggested 18 months for the first version of native rollups to be included in a fork; however, Uma Roy, co-founder of Succinct, said on Bankless she believes the ZK tech component may well be ready by then too.

What’s the difference between native rollups and based rollups?

A related concept is called a “based rollup,” which is where the L2s use Ethereum validators as a decentralized sequencer. This opens up the possibility of synchronous composability, which is a term that just means everything works together instantly across the ecosystem of based rollups.

It seems likely that many rollups will eventually become both based and native, which has been dubbed “ultra-sound” — although how long this will take to appear in the wild remains to be seen.

Also read: Ethereum L2s will be interoperable ‘within months’ — Complete guide

“Based rollups enable superpowers of synchronous composability,” says Ladislaus. “They are a bit of a harder sell because rollup teams have to give up current sovereignty over sequencing, but ultimately there are strong reasons to become based and native so that a rollup can be called an ‘ultra-sound rollup.’”

Not every rollup can become based and/or native, especially those that use a different virtual machine like Eclipse, which uses SVM; Starknet, which uses Cairo; and Movement, which uses MoveVM.

Rollups like MegaETH are also unlikely to ever become ultra-sound, as they rely on a single centralized sequencer, use alternative data availability and have no desire to sacrifice speed.

Subscribe

The most engaging reads in blockchain. Delivered once a

week.

Andrew Fenton

Based in Melbourne, Andrew Fenton is a journalist and editor covering cryptocurrency and blockchain. He has worked as a national entertainment writer for News Corp Australia, on SA Weekend as a film journalist, and at The Melbourne Weekly.