Security token offerings, or STOs, have more or less taken the mantle from their semi-defunct counterpart, the initial coin offering (ICO). Still, the extreme rise and subsequent fall of the ICO has left quite an impression on the cryptocurrency industry.

At its peak prevalence in 2017, this novel fundraising prototype accumulated a total of $6.2 billion — but it wasn’t set to last. Come December of the same year, ICOs had become a shadow of their former selves, plummeting in demand. So far, a mere $366 million has been raised via ICOs in 2019, a retrace of 94% from their high some two years prior.

This is perhaps a direct effect of the laissez-faire nature of ICOs. In 2018, the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) seemed to have decided that enough was enough, filing multiple injunctions against what it deemed to be “unregistered securities.” The clampdown had a double-whammy conclusion, simultaneously scaring off investors and disincentivizing projects.

Related: KIK Closes Messenger and Lays Off Staff to Continue SEC Lawsuit Fight

Much of the SEC’s butchery of ICO projects is still coming to light today. Just last week, Block.One, the software developer for EOS, settled a $24 million fine for refusing to register with the agency.

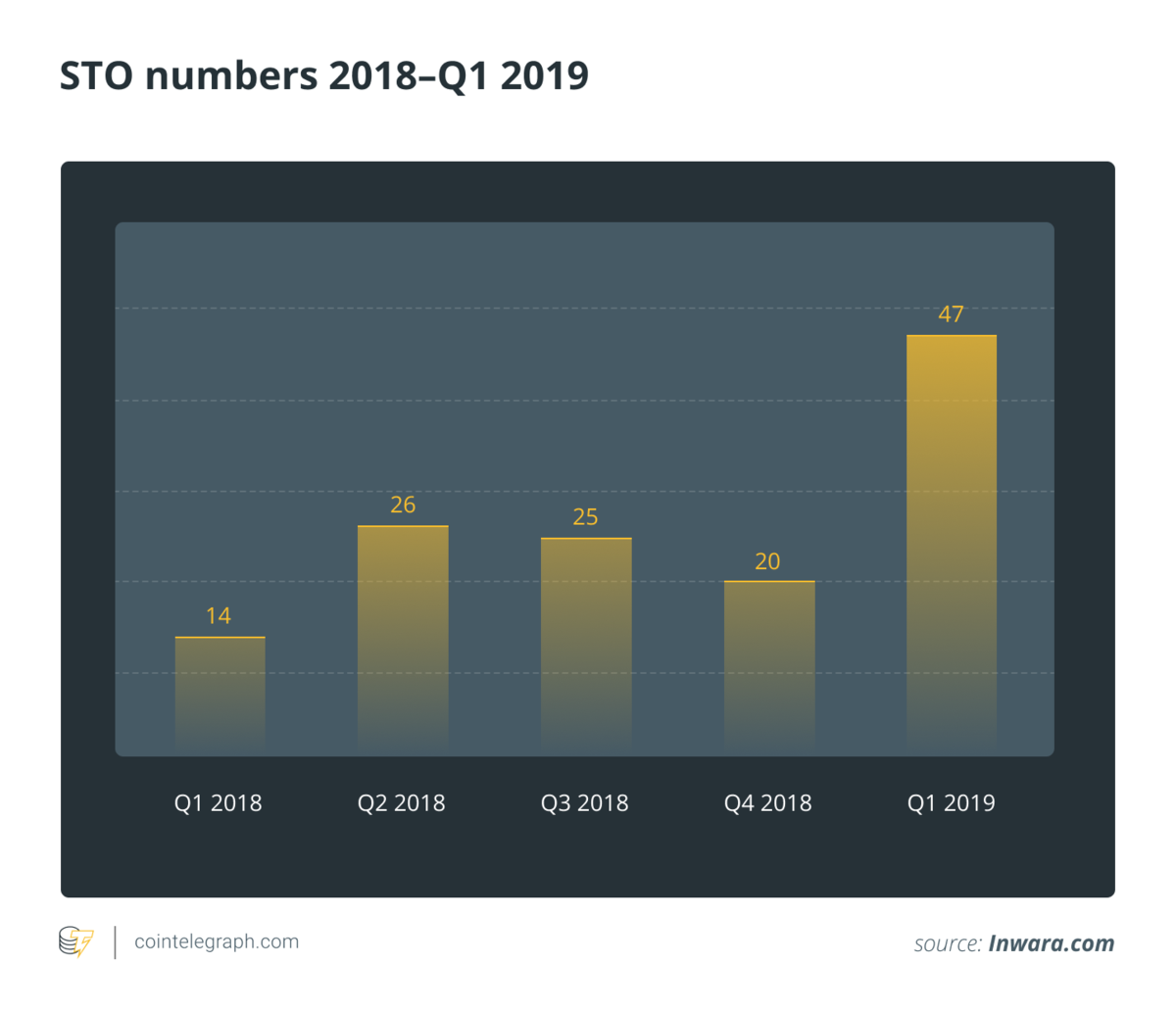

Another probable cause in the downfall of ICOs was the consequent rise of security token offerings. These offerings saw a shift in the paradigm of its predecessor, providing a sound regulatory model for investing on-chain.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given the SEC’s increased mindfulness as well as this renewed take on regulatory due diligence, STOs have shown a marked increase in the first quarter of 2019, expanding by an extraordinary 130%.

From the inside-out

Myriad issues still plague the regulatory landscape surrounding security tokens. Looking to quell these concerns is the recently established Japan Security Token Offering Association (JSTOA). Comprising several top Japanese securities firms including Rakuten, SBI, Monex, Daiwa and Nomura, the entity aims to enable member institutions to launch STOs within a reliable regulatory framework safely.

The JSTOA seeks to foster STO development by becoming a self-regulatory organization (SRO). To do so, the association will lobby for accreditation from the Financial Services Agency (FSA). Speaking to CryptoX, JSTOA secretariat and SBI representative Taira Takeda elaborated on the venture, pressing the importance of curated regulation:

“There is no regulatory standard about STO in Japan. So in JSTOA Japanese major Securities companies such as SBI, Nomura, Daiwa will discuss effective self-regulation based on their wealth of business experiences.”

Indeed, policy on the sale of cryptocurrencies remains reasonably stunted in Japan. It wasn’t until May 2019 that legislation was adapted to include crypto tokens within its framework. Both Japan’s Act on Settlement of Funds and its Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA) were amended to be inclusive of tokens.

In essence, rather than creating regulations based on the unique properties of each cryptocurrency — and, of course, STOs — the FIEA simply bundled them all under the existing securities law.

In light of this lax approach to security token regulation, the JSTOA formed, aiming to add clarity to existing governance by establishing itself as an SRO. As Takeda explained, the FIEA includes a clause that enables the formulation of more specific rules by certified self-governed organizations, essentially providing comprehensive policy autonomy:

“Though ‘Japanese Financial Instruments and Exchange Act’ defines STO as ‘Electronic Record Transfer Rights,’ a kind of securities, detailed rules about STO business are not determined. The Act determines that detailed rules should be enacted by SROs as self-regulations.”

Takeda also broached upon strategies for this regulatory sovereignty, citing influences such as the state-sanctioned U.S. regulator called the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), which is a nongovernmental organization that supervises financial entities all over the world.

SROs such as FINRA act as a creator and enforcer of regulatory standards, serving as a custodian against unruly industry business practices. Often, SROs — particularly financial watchdogs — establish requirements for member admission. For example, one fundamental prerequisite for FINRA registration is an examination of qualifications.

The admission criterion itself marks an essential advantage of SROs. Far from arbitrary entrance requirements made up by ill-informed bureaucrats, FINRA holds a relevant standard by which firms must abide. This is also true of self-devised rules and ordinances.

For the industry, by the industry

Regulation and the cryptocurrency industry have an incredibly mired past. It only takes looking as far as the policing of the crypto industry in the U.S. to comprehend the issues with government-mandated policy. Instead of a cohesive, symmetrical push on regulation, multiple agencies take on a piecemeal strategy, leading to a jurisdictional mismatch of policy that frustrates industry compliance.

It isn’t only companies that can profit from self-regulation, investors also gain from fitting policies. Governmental overregulation can sometimes occur in an effort to protect investors, which in turn increases production costs for businesses — costs that are usually transferred to clients.

Furthermore, it seems that the chances of a mass adoption may also be improved. Talking to CryptoX, Christophe de Courson, CEO of global asset management fund Olymp Capital, noted how the market entry of the JSTOA could bear a significant influence:

“The Association’s wide-ranging functions, including lobbying and promotion, will provide clarity and common understanding for crypto-players, investors, and regulators alike. Furthermore, it will put pressure on the Japanese Government to provide badly needed regulation for the cryptoasset space.”

Japan spearheading self-regulation

The JSTOA isn’t the first entity in the world to attempt self-regulation within the cryptocurrency industry. This isn’t the first attempt in Japan, either. Back in August 2018, the Japan Virtual Currency Exchange (JVCEA) was established, comprising 16 licensed cryptocurrency exchanges.

The association was swiftly certified by the FSA, marking it the first crypto-based SRO in Japan. This accreditation granted the JVCEA with sovereignty over domestic exchange legislation, something that was highly desirable following the $530 million Coincheck hack some seven months prior. During a briefing on the JVCEA, an FSA official highlighted the perks of self-regulation:

“It’s a very fast-moving industry. It’s better for experts to make rules in a timely manner than bureaucrats do.”

JVCEA’s accreditation, however, was no walk in the park. Its application to become an SRO underwent a fairly scrutinous two-month review by the FSA in order to verify its intent, so the JSTOA can likely expect as much from the same process.

Besides not being the first attempt at self-regulation, the JSTOA isn’t even the first shot at forming a security token association. Holding the accolade for pioneering the idea is the Japan Security Token Business Association (JSTBA). Apart from a slight variation in the acronym, it seems the JSTBA acts in much the same capacity as the JSTOA will. Both are — or aim to be — self-regulated organizations, with a focus on curating a standard to which providers of security tokens should uphold.

JSTBA membership already includes some of Japan’s notable names, including the cryptocurrency exchange CoinBene and the Japan EOS Developer Association (JEDA) Interestingly, the JSTBA noted that it is open to collaboration with other industry SROs, making it highly likely that there will be some cohesion with the emergent JSTOA.

Certainly, uniformity within cryptocurrency regulation would go a long way to remedy the current bottleneck of mismatched regulation. Speaking to Cointelgraph, Robin Matzke, co-founder of real estate crypto firm Fundament Group and an advisor to the German parliament, highlighted the importance of the JSTOA creating a precedent to follow:

“Collaboration and standardization is — generally speaking — always good in adopting new technologies or new methods. We hope this example will lead eventually to a more global approach on standards for securities that is not limited to specific countries.”

While a fair amount of good can be derived from self-regulation, it can also pose its own unique challenges and pitfalls. One major issue centers around anti-competitive behavior and the potential for an oligopoly. An unelected organization being handed legislative-like powers and free rein over which members to include and disbar could bear serious consequences. Speaking on the importance of trust within policymaking, Matzke noted that any regulation requires faith from all sides, with a critical goal in mind:

“Any form of regulation is important for industries that are built on trust — like the financial industry. In the end, it does not matter if it is self-regulation or governmental regulation. Regulation should always aim to best protect investors and be inclusive.”

Nevertheless, it’s reasonable that — given the broker’s existing positions and reputations within the financial sector as well as the established relationship between existing SROs and Japan’s FSA — such issues are unlikely to occur. As for whether self-governance is wise, the consensus for the time being suggests, yes. The establishing of concise cryptocurrency regulation stands as an integral part of the proliferation of the industry, and it seems as though change can only come from within.