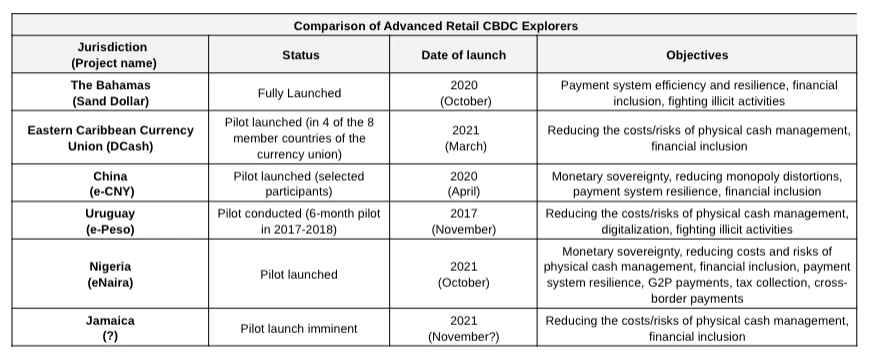

While much attention focuses on the retail central bank digital currency (CBDC) ruminations of China, Europe and the United States, smaller jurisdictions are leading the way. For example, Uruguay, the Bahamas, the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, Nigeria and Jamaica have each launched pilot CBDCs over the past three years.

The potential benefits of CBDCs are numerous – from automating certain tax payments to preserving a nation’s monetary sovereignty – if only theoretical at this stage. The idea is to revamp a crucial part of society, how money is issued and flows through an economy, and so, even small design choices can have substantial effects.

So central banks are proceeding carefully, but given the amount of intellectual effort being expended, it’s likely CBDCs will have a place in the global financial system.

This article is part of CryptoX’s Future of Money Week, a series exploring the varied (and sometimes weird) ways value will move in the future.

Overview of the CBDC landscape

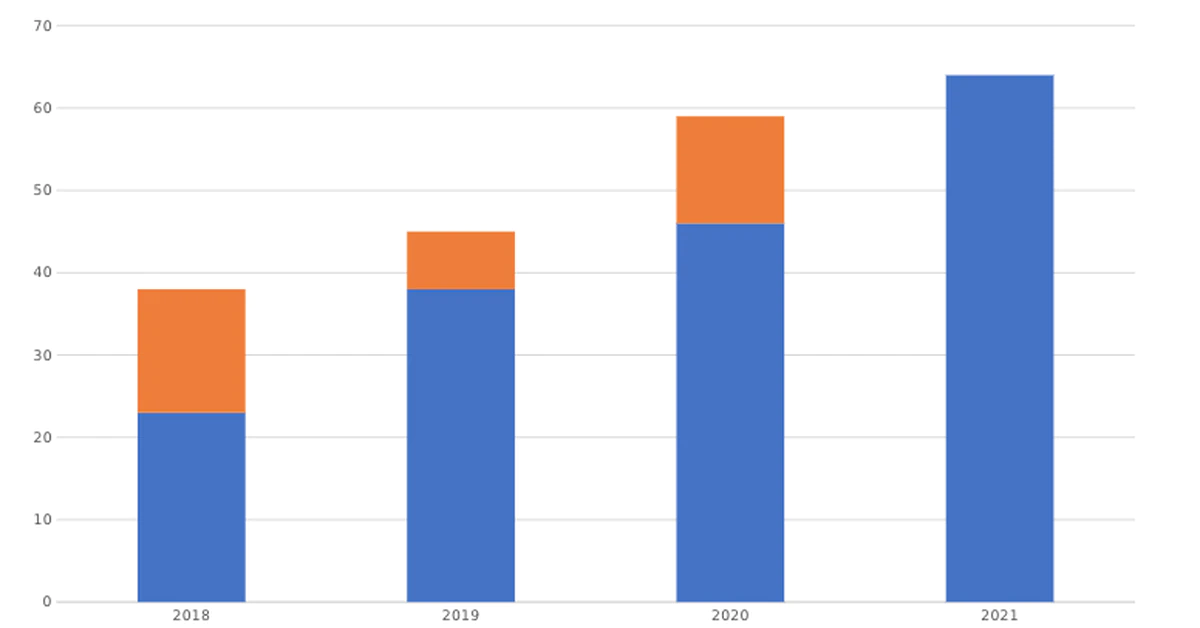

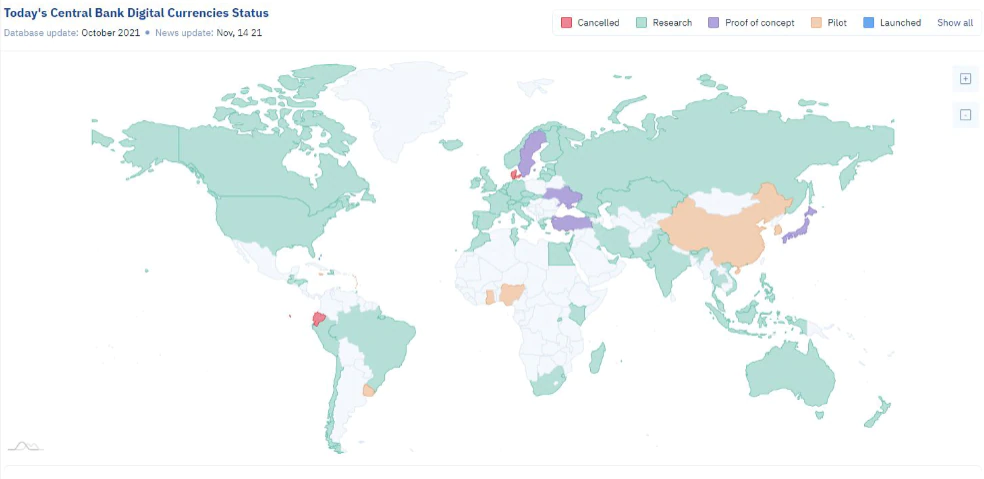

According to our CBDC Tracker, there are currently at least 64 central banks exploring retail CBDC, of which 20 have either launched, piloted or are in the very advanced exploration stages. We say “at least” because our count is based on reliable public sources (almost all from the central banks themselves). However, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 58 of the 65 central banks surveyed at the end of 2020 were exploring retail CBDC. In any case, the growth in the number of retail CBDC explorers has been remarkable.

It is important to be clear as to what is and is not retail CBDC. The BIS defines retail CBDC as a broadly available general purpose digital payment instrument, denominated in the jurisdiction’s unit of account, that is a direct liability of the jurisdiction’s monetary authority. There is also wholesale CBDC, which is limited to a set of predefined user groups, typically financial institutions. That’s not what we’re talking about here. Also the “direct liability of the monetary authority” condition precludes the Marshall Islands SOV and Cambodia’s Project Bakong.

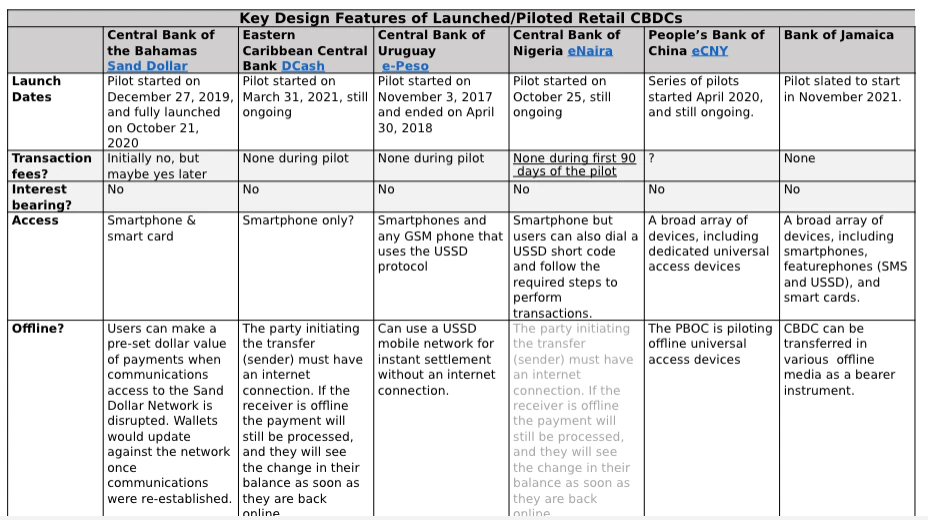

There are six jurisdictions that have either fully launched (Bahamas) or have launched pilots (China, Eastern Caribbean Central Bank, Jamaica, Nigeria and Uruguay). Another 14 are in the advanced stages of retail CBDC research, of which six have started or soon will start proofs of concept (Bhutan, Ghana, Japan, Korea, Sweden and Ukraine). Proofs of concept differ from pilots as the former takes place in a laboratory environment (e.g., among central bank staff) and the latter involves “real world” testing, typically among limited populations.

The vast majority of central banks studied are in an exploratory stage, typically consisting of desk research and perhaps some reaching out to technology platform providers. Some in this group may actually belong in the “advanced” group, but we have no direct evidence of that based on central bank communication.

Motivations

For emerging market and developing economy (EMDE) countries, some of the main motivations for launching or piloting a retail CBDC are financial inclusion and payment system efficiency, including reducing the costs/risks of managing physical cash and higher payment system resilience/safety. Fighting illicit activities is another key theme. Protecting monetary sovereignty, whether it be pushing back on dollarization or the encroachment of private digital currencies such as the Facebook-initiated diem project, is a common theme among both EMDE and advanced economy (AE) central banks.

For China and some other AE central banks that have not yet launched pilots, reducing the monopoly powers of private payment systems (e.g., AliPay and WeChat Pay in China) are important retail CBDC exploration motivations.

Design choices

Retail CBDC design choices depend on policy objectives and country specifics, but among those retail CBDCs that have launched, there is a high degree of high-level commonality.

Business models

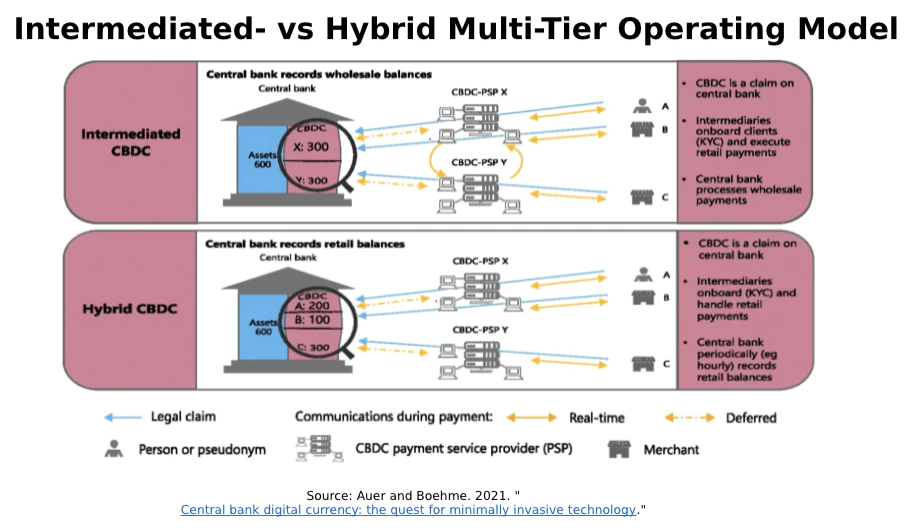

In a single-tier model the central bank performs all the tasks involved, from issuing and distributing the CBDC to running user wallets. In multi-tier models, the central bank issues and redeems CBDC, but distribution and the operation of payment services would be delegated to private sector payment service providers (PSPs). Which model to adopt will depend on country-specifics, such as financial sector breadth and depth, financial integrity standards, compliance, financial market infrastructure availability and supervision capacity.

All retail CBDCs that have launched or piloted run on multi-tiered business models of the “intermediated” variety, as described in a recent BIS paper. In this variation, PSPs back the CBDC they distribute in wholesale accounts at the central bank, which has no direct record of individual CBDC holder balances. However, the central bank maintains a backup copy of individual balances they would use to restart payments should a PSP fail. Presumably, the PSP’s CBDC wholesale account is legally ring-fenced from the PSP’s other operations and immediately available to the central bank in such an event. So far, no central banks have opted for a “hybrid” model where the PSPs are merely agents on behalf of the central bank.

Holding/transaction limits

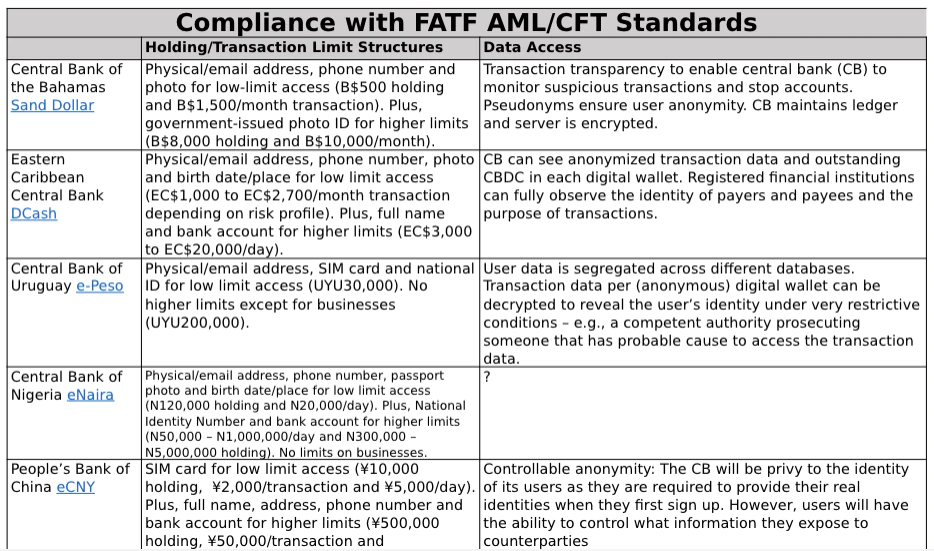

Central banks face a CBDC design trade-off between satisfying user preferences for privacy and giving authorities access to user identities and transaction data to mitigate the risk of illicit financial activity. Privacy preferences may be driven by fear of spamming and identity theft, and of being stalked or robbed. Also, a fully transparent CBDC might raise digital surveillance concerns, especially in jurisdictions where trust in public institutions is low. Such CBDC might disadvantage those without access to identification. However, most central banks are effectively obligated to meet the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) anti-money laundering and countering terrorist financing (AML/CFT) standards.

Almost all central banks that have launched retail CBDC have taken similar approaches to applying “proportionality” to their compliance with FATF AML/CFT standards, by allowing for more privacy on low-value holdings/transactions.

For example, China’s eCNY users are identified only by their mobile phone SIM cards for the lowest tier of access (a holding limit of ¥10,000, and transactions are limited to ¥2,000 up to ¥5,000 per day). However, by providing full names, addresses and phone numbers, and by linking the CBDC wallet with their bank accounts, limits increase substantially (¥500,000 holding, ¥50,000 per transaction and ¥100,000 per day). Jamaica is the exception, in that there are no limits on CBDC holdings or transactions, but all holders face full-blown know-your-customer (KYC) requirements. Also, central banks typically have access only to pseudonymous data, but in some cases can de-anonymize it if they can show probable cause (e.g., with a court order).

Other design choices

In terms of the main design features of retail CBDCs that have been launched and piloted, none of them pay interest, charge transaction fees or incorporate smart contracts capabilities. So far, only the People’s Bank of China seems to be experimenting with totally offline retail CBDC payments and programmability of payments. However, the Bahamas Sand Dollar can effectively be used by users when they are abroad through a MasterCard prepaid card, but receivers get their own national currency in payment, not Sand Dollars.

A diversity of technical platforms, both centralized and distributed ledger technology (DLT) based, have been deployed, although those adopting DLT have opted for the private permissioned network variety, mainly based on Hyperledger Fabric, an open source blockchain framework hosted by The Linux Foundation. The latter allows for control over platform participants and their access to the platform, and role-based oversight and visibility of transactions. Private permissioned platforms also ensure that the central bank retains full control over money issuance and monetary policy. Again, Jamaica is unusual in that its retail CBDC doesn’t use centralized or decentralized ledger technology. Instead, it is a ledgerless digital bearer instrument.

What’s in the pipeline

Most of the 12 central banks that are known to be in the advanced stages of retail CBDC deliberations view retail CBDC as a contingency plan. For example, Bank of Canada officials have said that a digital loonie could be launched if cash usage continues to decline and/or stablecoin usage accelerates. The European Central Bank (ECB) has a similar view on its digital euro.

Although the U.S. Federal Reserve is conducting a major retail CBDC research program, board member Christopher Waller has described a digital dollar as a “solution in search of a problem.” As CryptoX columnist J.P. Koning points out, for several AE countries, “everything that a CBDC is supposed to fix can already be achieved by another existing process or institution – and these alternatives are typically cheaper and less risky.”

And even if some AE country central banks move in the direction of issuing retail CBDC, the road there will be long and ponderous. The Bank of England has said that if the results of their development work “conclude that the case for CBDC is made, and that it is operationally and technologically robust, then the earliest date for the launch of a UK CBDC would be in the second half of the decade.” The ECB has said that a digital euro could come in 2026 at the earliest.

Nevertheless, because AE country central banks are so transparent in their deliberations, versus the stealthier EMDE countries, we know a lot about what might be coming down the retail CBDC pipeline.

Also part of Future of Money Week:

7 Wild Scenarios for the Future of Money – Jeff Wilser

The Downside of Programmable Money – Marc Hochstein

Ethereum in 2022: What Is Money in the Metaverse? – Edward Oosterbaan

The Future of Money: A History – Dan Jeffries

Remunerated retail CBDC

Some academic research advocates paying variable interest rates to CBDC holders to modulate demand or provide a new monetary policy instrument. For example, an interest-bearing retail CBDC could enhance the transmission of monetary policy by increasing the economy’s response to policy rate changes. Such a CBDC could be used to break the “zero lower bound” on policy rates to the extent that cash was made costly. Also, an ECB working paper has suggested a tiered remuneration system with relatively attractive interest rates on small holdings, and lower rates on large ones, to mitigate the risk that the CBDC disintermediates the private banking system.

Offline access

According to a 2020 Bank of Canada note, a resilient and inclusive retail CBDC should serve people without smartphones, support online and offline transactions, and be able to operate for long periods on a local power source. To meet these requirements, the bank is investigating the idea of a “universal access device” (UAD) that could take the form of a card or mobile wallet app on which prepaid values are stored locally. Rohan Grey adds that such devices could also be designed to maintain the same transactional freedoms and functions in the digital space as physical cash in the traditional economy. The concept isn’t completely new – several such devices were introduced in some AE countries a few decades ago (e.g., Mondex and VisaCash) but they failed to develop much customer acceptance. However, a UAD could be of interest for EMDE countries where large population segments are excluded from the formal financial sector or internet access.

Smart contracts

A 2020 Bank of England paper discusses how smart contracts may enable the development of programmable payments to automatically execute terms of an agreement and initiate related transactions without human intervention. Potential applications here include paying sales taxes directly to tax authorities at point of sale and integration with physical devices or internet-of-things (IoT) applications. Embedded smart contracts could also be used to implement targeted aid payments that can be spent only on predefined goods and services. However, the People’s Bank of China suggests that smart contracts could undermine the CBDC’s legal tender status, and, in the worst case, reduce the CBDC to a form of negotiable security that may affect its free usability.

What’s next?

Going forward, we will likely see more EMDE central banks than AE ones pilot testing and launching CBDCs, with many of the former coming seemingly out of the blue from among the 44 central banks that we have labeled as being in the exploratory stage. This is because the benefits of introducing CBDCs are typically more obvious in EMDE countries, providing substantial benefits that seemingly outweigh the risks. For example, increasing financial inclusion and decreasing cross-border payments costs are high policy priorities in EMDE countries.

AE central banks, on the other hand, take a more cautious approach. They are mainly in the process of investigating the potential benefits of a CBDC and studying risks carefully. In particular, they assess risks to the financial sector in detail, as AE central banks place a high priority on preserving financial stability. They will likely continue their more transparent, but slower efforts, and it’s no sure thing that many of them will launch.

One exception is China. Here, a CBDC will likely be introduced in the first quarter of next year, right on time for the Winter Olympics in Beijing. From an economic perspective, the Chinese CBDC will provide essential insights for decision-makers in AEs that are currently still not sure whether to issue a CBDC.