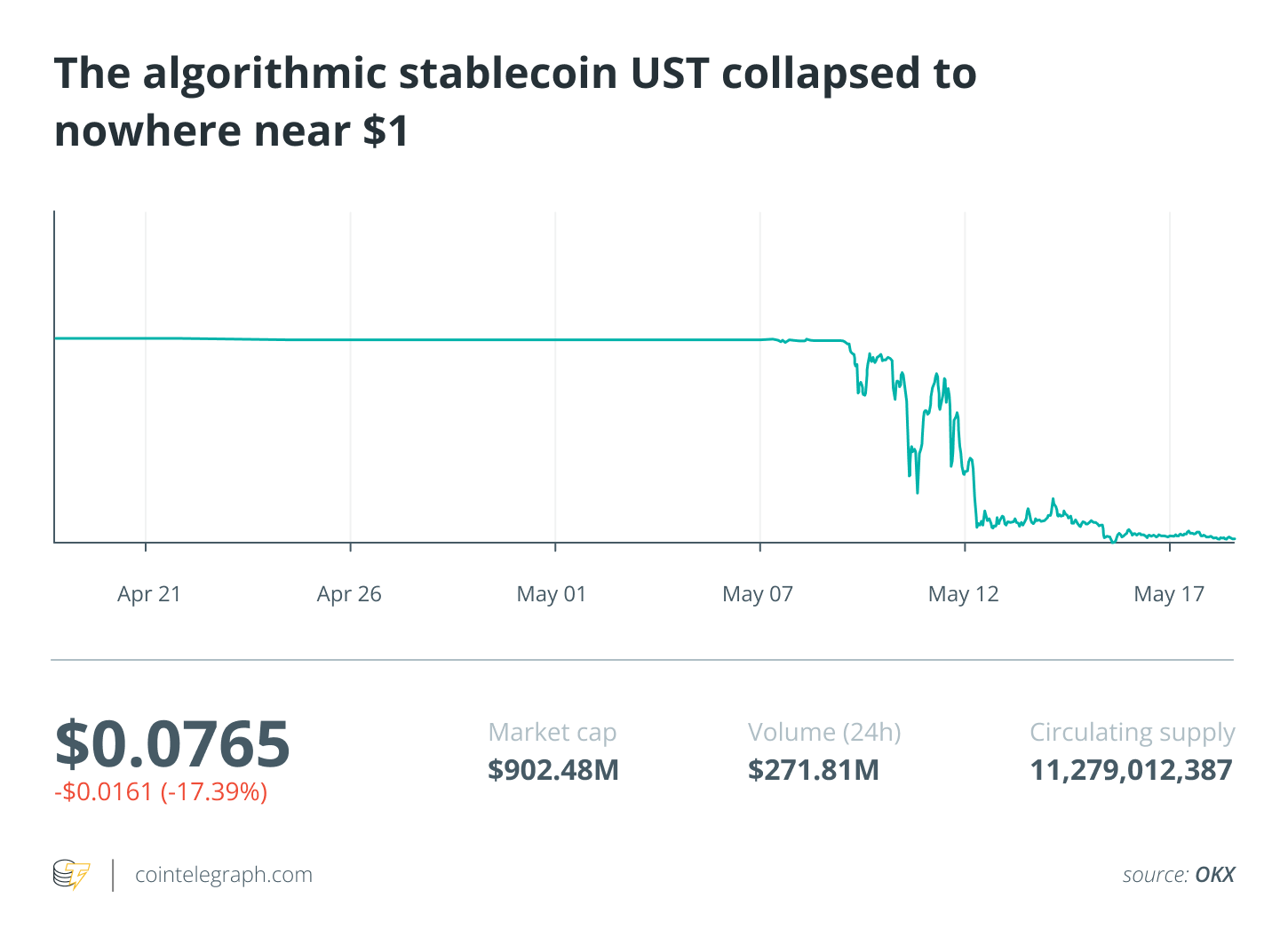

The spectacular implosion of the Terra ecosystem in mid-May left the crypto industry scarred. Though there were some brave critics who understood just how thin the razor’s edge was for TerraUSD (UST) — now TerraUSD Classic (USTC) — I think it’s safe to say that most people didn’t expect Terra to fail so fast, so dramatically and so completely irrevocably.

I’m writing this as the Terra community is voting on a plan to restart some kind of Terra 2.0 — a plan to salvage the layer-1 ecosystem without the UST stablecoin. The old Terra, now to be known as Terra Classic, is completely dead. An ill-fated attempt to backstop UST holders printed trillions of LUNA tokens, destroying their value and ultimately jeopardizing the safety of the network itself.

The complete wipeout of $50 billion in value seems to have made people decide once and for all that algorithmic stablecoins cannot work. But I think it’s important to have a more nuanced understanding of why the original LUNA failed and how others can learn from its lessons.

Related: Terra 2.0: A crypto project built on the ruins of $40 billion in investors’ money

Stablecoins: New name for an age-old concept

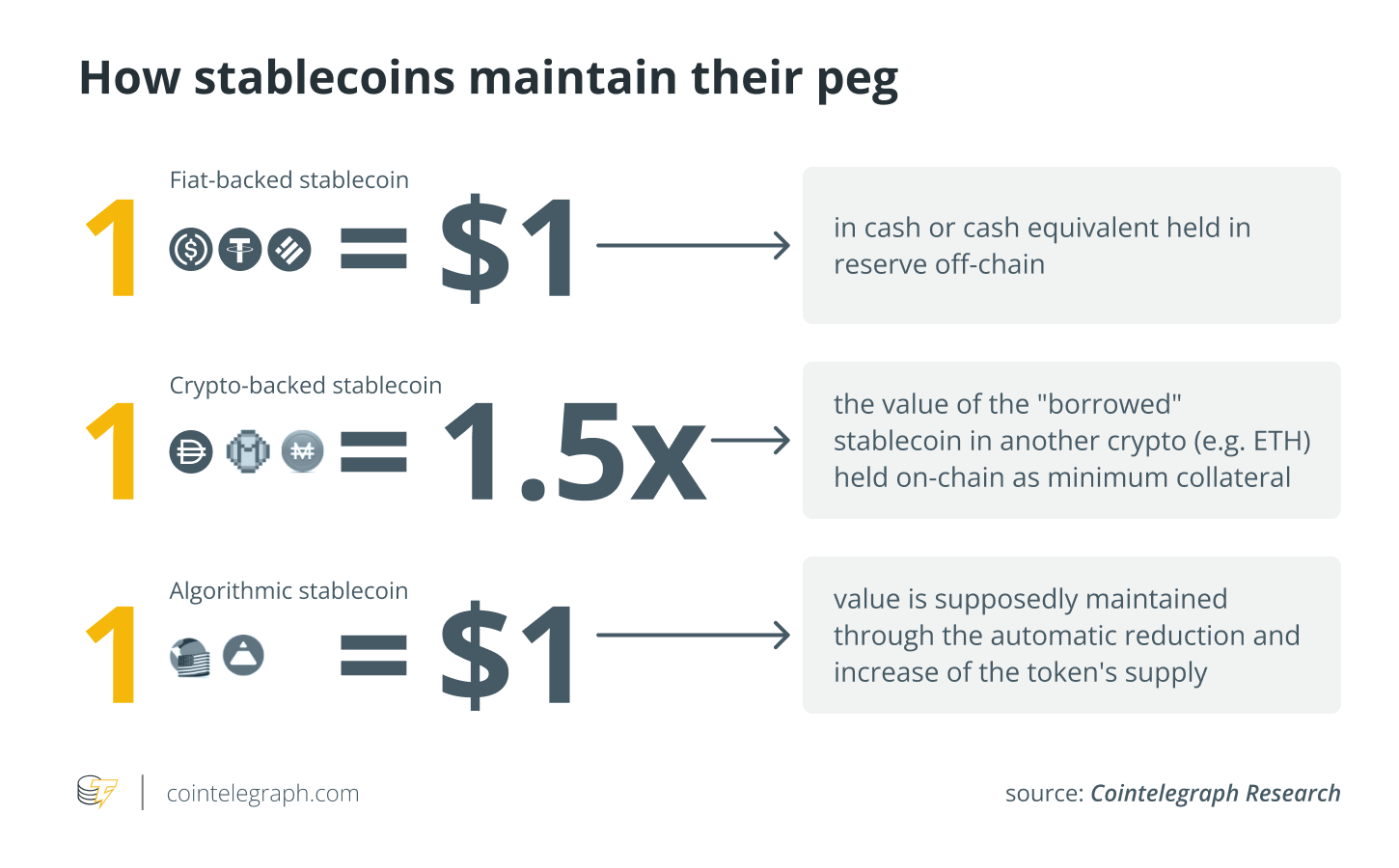

The term stablecoin mostly evokes United States dollar-pegged currencies that aim to maintain a $1 value. But it’s important to remember that this is mostly a matter of convenience. The same mechanisms underpinning today’s USD stablecoins can be used to create coins that are pegged to the euro, gold, even Bitcoin (BTC), Nasdaq futures, or some specific stock, such as Tesla (TSLA).

It’s also interesting to note that stablecoins are not really a new crypto idea. Today’s stablecoin designs are closely related to either how money works under a gold standard — e.g., Maker’s Dai is a claim to a hard collateral just like early banknotes were claims to a gold vault — or they’re a reproduction of pegged currencies such as the Hong Kong dollar.

The HKD is a very interesting example in all of this because it’s pretty much your run-of-the-mill “algorithmic stablecoin.” It’s pegged to the U.S. dollar, even if not at a 1:1 ratio, and the HK central bank uses its vast reserves to keep HKD’s price in a well-defined ratio by trading it on the market. The latest audits place the Hong Kong reserves at $463 billion, which is six times the HKD in immediate circulation and almost half of its M3, the broadest definition of “money” that also includes not immediately liquid assets (like locked bank deposits).

Really the only reason why HKD is technically not an algorithmic stablecoin is that there is a central bank conducting market operations. In decentralized finance (DeFi), the central bank is replaced by an algorithm.

Related: UST aftermath: Is there any future for algorithmic stablecoins?

Terra ain’t no HKD, though

Conflating Terra with the algorithmic stablecoin space, in general, fails to see why Terra collapsed as hard as it did. It’s important to realize just how fragile the Terra protocol design was. In a nutshell, UST was “collateralized” by LUNA, the gas token of the Terra blockchain. Since there was a fairly solid DeFi and nonfungible token ecosystem developed on Terra, the LUNA token had some inherent value that helped boost the initial supply of UST.

The way the mechanism worked was, in principle, similar to HKD. If UST traded above $1, users could acquire some LUNA and burn it for its dollar value in UST. Crucially, the system assumed that UST was worth $1, so the LUNA burner can just sell the UST on the market for, say, $1.01 and make a profit. They can then recycle the profits into LUNA, burn it again, and continue the cycle. Eventually, the peg would be restored.

If UST traded below $1, the reverse mechanism helped backstop it. Arbitrageurs would buy the cheap UST, redeem it for LUNA at a rate of 1 UST equaling $1, and sell those tokens on the market at a profit.

This system is great at keeping the peg in normal circumstances. One issue with Dai, for example, is that it can’t be directly arbitraged for its underlying collateral. Arbitrageurs need to “hope” that the peg stabilizes to make a profit, which is the primary reason why Dai is so reliant on USD Coin (USDC) now.

But we also need to mention the extreme reflexivity in Terra’s design. Demand for UST that makes it go above peg results in demand for LUNA, and thus, an increase in price. The keystone of this mechanism was Anchor, the lending protocol on Terra that guaranteed a 20% APY to UST stakers.

Where did the 20% APY come from? From extra UST minted through Terraform Labs’ LUNA reserves. A higher price of LUNA meant that they could mint more UST for Anchor yield, thus increasing UST demand and increasing LUNA’s price — thus they were able to mint even more UST…

UST and LUNA were in a cycle of reflexive demand that, let’s face it, had all the elements of a Ponzi. The worst thing was that there was no cap on how much UST could be minted as, say, a percentage of LUNA market capitalization. It was purely driven by reflexivity, which meant that just before the crash, $30 billion in LUNA’s market cap backed $20 billion in UST’s market cap.

As Kevin Zhou, founder of Galois Capital and a famous critic of LUNA and UST before it collapsed, explained in an interview, each dollar put into a volatile asset raises its market cap by eight or more times. In practice, this meant that UST was wildly undercollateralized.

Based on his calculations, @Galois_Capital‘s Kevin Zhou believes that $4-$5B in liquidity will leave UST if the yields on Anchor are cut down to 7-12%, which he estimates could lead to an 8x decompression of the LUNA price. What do you think of his math? https://t.co/pnlLHHXtkM pic.twitter.com/oAhNCvTgim

— Laura Shin (@laurashin) April 8, 2022

Pricking the bubble

It’s difficult to pinpoint the specific reason why the collapse began when it did, as there were definitely multiple factors ongoing. For one, Anchor reserves were visibly depleting, with only a couple of months worth of yield remaining, so there was talk of reducing the yield. The market was also not doing too well, as most large funds began to expect some kind of large crash and/or protracted bear market.

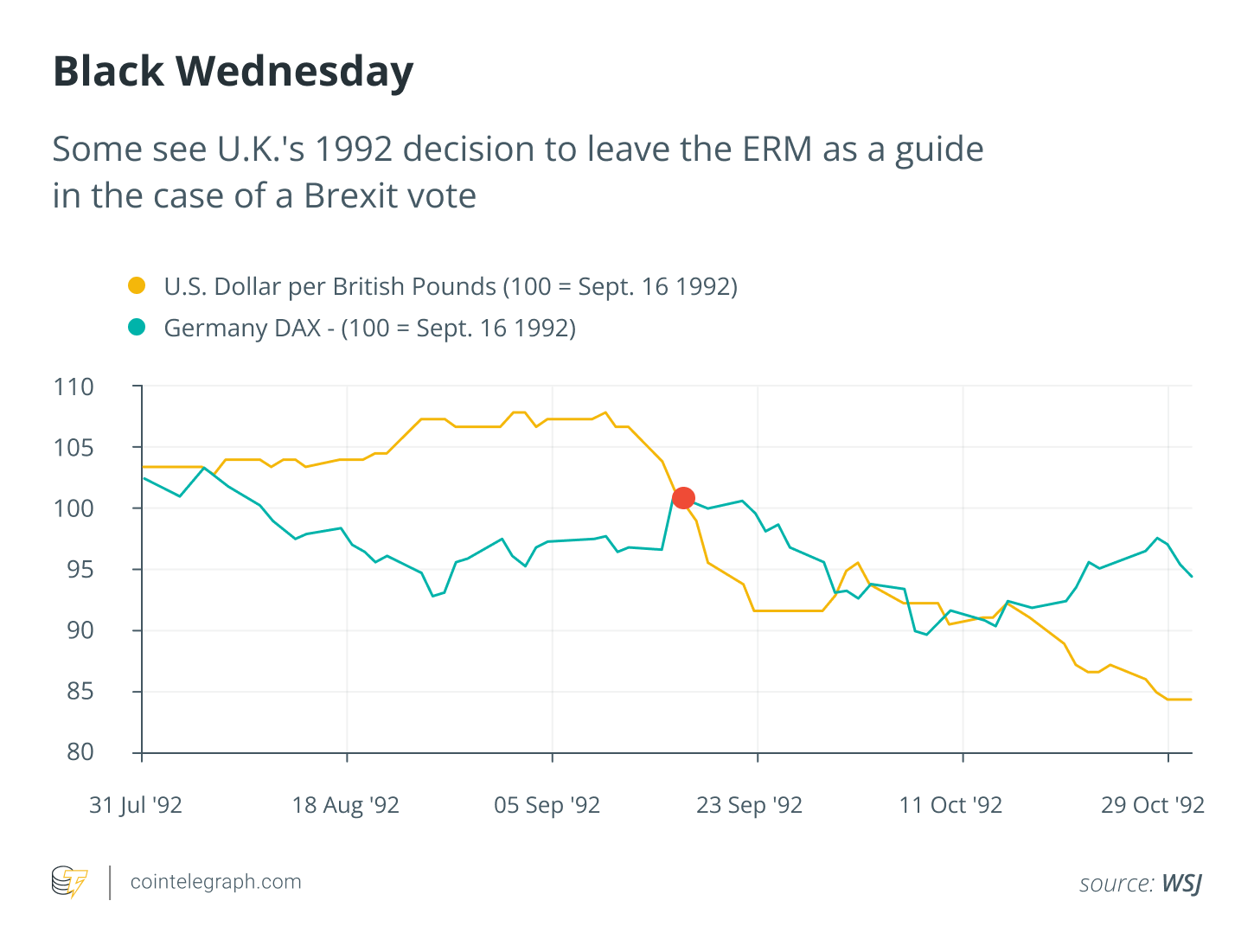

Some conspiracy theorists blame TradFi giants like Citadel, or even the U.S. government, for “shorting” UST with billions and triggering the bank run. Be that as it may, this is crypto: If it’s not the U.S. government, it’s going to be some rich whale who wants to be known as the second coming of Soros (who famously shorted the British pound when it had a similar peg setup, known as the Black Wednesday. While not as dramatic as Terra, the pound did lose 20% in just about two months).

In other words, if your system can’t handle coordinated and well-funded attacks, it probably wasn’t a good system, to begin with.

Terraform Labs sought to prepare itself for the inevitable, collecting a total of just about 80,000 BTC that were supposed to backstop the peg. It was worth about $2.4 billion at the time, not nearly enough to redeem all UST holders who wanted to exit.

The first depegging event between May 9 and 10 took UST to about $0.64 before recovering. It was bad, but not deadly just yet.

There is an underappreciated reason why UST never recovered. The LUNA redemption mechanism I explained earlier was capped at about $300 million per day, which was ironically done to prevent a bank run for UST from destroying LUNA’s value. The problem was that LUNA collapsed anyway, quickly going from $64 to just about $30, which already shed $15 billion in market capitalization. The depeg event barely shed any UST supply, as more than 17 billion remained out of an initial 18.5 billion.

With Do Kwon and TFL being silent for the next few hours, the price of LUNA continued its collapse without any meaningful redemption activity, going to single-digit lows. It was only here that the management decided to up the redemption cap to $1.2 billion when LUNA’s market cap had already fallen to $2 billion. The rest, as they say, is history. This rushed decision sealed the fate of the Terra ecosystem, resulting in hyperinflation and a later halt of the Terra blockchain.

Related: Terra’s meltdown highlights benefits of CEX risk-management systems

It’s all about the collateral

Successful examples from TradFi like HKD should be a clue to what happened here. Terra appeared to be overcollateralized, but it really wasn’t. The real collateralization before the crash amounted to maybe $3.6 billion (the Bitcoin reserves plus Curve liquidity and a couple of days worth of LUNA redemptions).

But even 100% is not enough when your collateral is as volatile as a cryptocurrency. A good collateral ratio could be between 400% and 800% — enough to account for that valuation compression Zhou mentioned. And smart contracts should rigorously enforce this, prohibiting new coins from being minted if the collateralization is not ideal.

The reserve mechanism should also be maximally algorithmic. So, in the case of Terra, the Bitcoin should’ve been placed in an automatic stabilization module instead of opaque market makers (though here, there just wasn’t enough time to build it).

With safe collateralization parameters, a bit of diversification and a real use case for the asset, algorithmic stablecoins can survive.

It’s time for a new design for algorithmic stablecoins. Much of what I recommended here is contained in the Djed white paper that was released a year ago for an overcollateralized algorithmic stablecoin. Nothing has really changed since then — the Terra collapse was unfortunate but predictable, given just how undercollateralized it was.

This article does not contain investment advice or recommendations. Every investment and trading move involves risk, and readers should conduct their own research when making a decision.

The views, thoughts and opinions expressed here are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect or represent the views and opinions of Cryptox.

Shahaf Bar-Geffen has been the CEO of Coti for more than four years. He was also part of the Coti founding team. He is known as the founder of WEB3, an online marketing group, as well as Positive Mobile, both of which were acquired. Shahaf studied computer science, biotechnology and economics at Tel-Aviv University.