America’s K-12 education system often gets a bad rap. It is obsessed with standardized tests and accountability. Those tests mean what kids learn in classrooms is seriously focused on preparing for those tests and overweighting a student’s experience toward narrow content rather than engaging experiences. Employers and universities say kids leave high school unprepared with skills like communication and critical thinking needed to function and thrive in higher education and at work. Students themselves often feel unprepared for the world they face, which makes them anxious and unhappy.

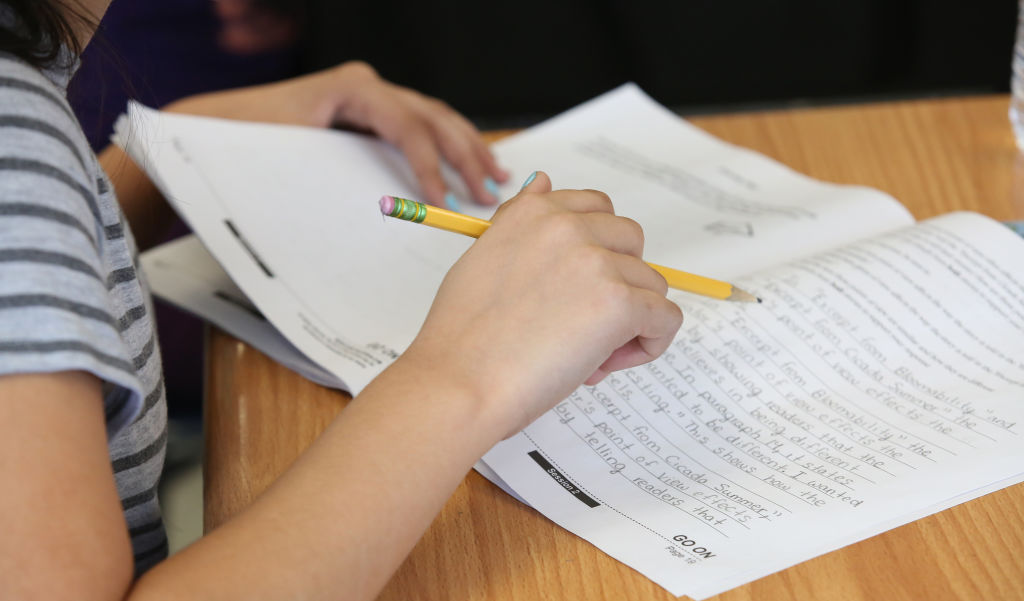

At the core of many of these critiques is the architecture of learning. Kids are required to spend a certain amount of time in class every year (about 1000 hours of instruction per year, or some close variation of that). Time defines their learning more than whether they are actually learning. “Seat time is the rule,” says Timothy Knowles, president of the Carnegie Foundation for Teaching and Learning. “Mastery or competence is not the rule.”

That is starting to change.

Earlier in 2023, the Carnegie Foundation teamed up with ETS, the nonprofit testing giant that writes and administers tests like the GRE, to start rebuilding those architectural foundations. First, they plan to dismantle something called the Carnegie Unit, which since 1906 dictated how schooling works by defining how much learning has to take place in a year, or to award a particular degree (for instance, the number of college credits to graduate is based on the Carnegie unit). Second, they will build a new suite of skills-based assessments to measure competencies and mindsets such as collaboration, critical thinking, creativity, and communication or perseverance and empathy.

The implications of this shift are huge. Learning science—and common sense—has long established that kids learn everywhere, not just in school, and they acquire all sorts of skills and abilities that are hard to see because they are not measured in any valid, reliable, shareable, or understandable way. Many kids develop world-class time managements skills—the ability to manage a job, care for siblings and succeed without high-priced tutors or deep social networks. But those skills are not reflected in assessments to colleges or employers in meaningful ways and should be. Kids with access to lots of AP classes, and lots of AP tutors are rewarded while those with resilience and equal academic ability are overlooked.

“If we can build tools that see the unseen, that capture authentic representations of learning wherever it happens, the opportunity is to help propel and elevate, amplify millions more young people,” says Knowles.

If developed well—a massive if—a new way to measure learning could make that learning more relevant, more engaging, less opaque, and more equitable.

Read More: Americans Have No Idea How Their Kids Are Doing in Schools

Start with the benefits to students themselves. Skills assessments would help kids and families know more about their learning. Can my child communicate effectively? Work with others well? Think about problems rather than simply fill in a bubble? Such tests would provide teachers with reliable, valid, research-backed tools to reinforce what they already do, which is encourage the development of these skills with little support or research. It will give universities and employers a richer set of data from which to select students.

“Everywhere you look in education, the outcomes of the current K-12 and higher education system are at best, uneven, and at worst, completely failing,” says Amit Sevak, CEO of ETS, the billion-dollar nonprofit testing giant. “We’re focusing on ‘did you get an A or B’, in biology, or science if you’re an elementary or middle school, as opposed to what are the underlying skills that are actually going to have relevance for the world of work and in society?”

Competency-based learning is not new. But it has existed on the fringe of K-12 education, not at the heart of it (it is well-established in fields like medical school).

But by teaming up with ETS—a key player in the “failing” status quo—Carnegie hopes to bring it mainstream.

Superintendents, teachers and education leaders support the change. “I’m thrilled that they’re finally having this long overdue conversation,” says Dr. Tamara Willis, superintendent of Susquehanna Township School District in Pennsylvania. “We in the K 12 space are starting to realise that we have to rethink how we are educating our students and how we’re preparing them for life after graduation, or for their post-secondary options that seemed to kind of broaden with each new day.”

Imagine a math class of 30 kids. A teacher’s goal is to get as many of them to “proficiency” as possible, with the teacher, the school and the district are all held accountable for it. So the teacher preps for the test the easiest way possible: test prep. The problem? A lot of kids don’t like test prep, because it can be boring, and many kids don’t test well. “There’s a ton of research that shows that sitting down and taking a one and done type of exam is not the best suited for our learners,” says Anibal Soler, superintendent of the Schenectady City School District in New York. “Superintendents, state education department, so many of us are asking the question, ‘Are these assessments, the right assessments’?”

Now imagine that inside that math class you aim to develop collaboration skills. You identify the competencies which underpin collaboration—maybe listening, taking feedback and offering it. Students have a digital portfolio, or wallet, in which they keep track of their collaboration (and other skills). In identifying the skills and the ways to develop them students start to notice them. Teachers add to the portfolio. Parents do too. Key to the effort is that kids are not ranked and sorted based on their creativity or empathy, which would no doubt lead rich parents to immediately hire and army of empathy tutors.

The goal is not performance, but growth.

Many states like Kentucky, New York, and Michigan have worked with parents, teachers and communities to agree on the skills young people need to survive and thrive in a fast-changing and uncertain world. They call them Learner Profiles or Profiles of a Graduate. Northern Cass School District #97 in Iowa identified five: accountability, communication, adaptability, leadership and learner mindset. The district doesn’t rank kids on adaptability but rather teaches students how to develop it. “We don’t assess those skills,” says Dr Corey Steiner, superintendent. “We only give feedback.”

Read More: The Politics of Fear Is Damaging American Education

Northern Cass has moved entirely from a grades-based system to one that measures proficiency. Most districts would be more likely to use skills-based assessments as an add on rather than a replacement, a way to make sure the skills get recognized and measured officially, like academics, and not accidentally. This opens up choice for students: those who want to pursue college do so with academic credentials. Those who want to pursue vocational learning, coding bootcamps, welding, Google’s credentialing, or any other alternate pathway will also have data on skills and abilities acquired.

There is ample demand for more recognition of what kids know, and can do versus what a school says they can do. Partly that’s because epic grade inflation has made it impossible to know what grades means. “I’ve been in this game a long time and I don’t know what a 90% means,” says Northern Cass’ Dr. Steiner. A child brings in food for a fundraiser and gets five bonus points and that’s an A, he says. Or they turn in a paper late with 100% on content but get marked down for tardiness. No one except the teacher understands what that child can actually do.

But also, the system has not prioritized skills development. According to a 2019 study from the National Association of Colleges and Employers, the majority of employers believe that critical thinking problem solving and teamwork are essential skills for workforce performance but college graduates lack them. The World Economic Forum regularly surveys global companies to ask the skills they are hiring for today and want for the future. The ones on the rise include creative thinking and analytical thinking—with “curiosity and lifelong learning” close behind. How does an A in math lend itself to lifelong learning?

Internationally, efforts to measure broader skills are decades old. The OECD administers the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), a test of reading and math, and science taken by 500,000 kids in 79 countries every three years. Since 1997 it has been developing optional tests to complement the academic ones, including ones to measure collaborative problem solving, global competencies and creative thinking. “The advent of AI should push us to think harder of what makes us human,” said Andreas Schliecher, the head of the education unit of the OECD. If we are not careful, the world will be educating “second-class robots and not first-class humans.”

There are many groups in the U.S. doing similar work, but none at massive scale. The Competency Based Learning Network and the Aurora Institute have long championed better, richer learning experiences for students and developed tools to measure and capture their progress. The Mastery Transcript was created in 2017 to address the fact that colleges needed a way to understand different forms of assessment beyond the SAT and GPA. The American Council on Education translates military experience, or certifications like those issued from Google or IBM, into college credit, showing that such work is both possible and well underway.

Those efforts remained at the edges until COVID-19 and AI created the conditions to change that. COVID let parents into the black box of education and many did not like what they saw. The explosion of generative AI highlighted the importance of uniquely human skills beyond math and reading and science (which ChatGPT can do very well). It also improved the tools to do so: generative AI can help create assessments to give in natural settings—not in an auditorium on a given Tuesday— and over time.

There are significant risks to trying to reshape America’s industrial test complex. By standardizing human skills to assess them we run the risk of de-humanizing them. A balance of skills and academics will have to be struck rather than piling more assessments onto already-stressed out kids and overburdened teachers. The focus will need to be on the development of skills, not the ranking and sorting of them. The acquisition of core academic knowledge should not be thrown out in a bid to make kids employable.

For example, a skill like collaboration might entail being a good listener; being able to exchange ideas respectfully; and being able to accept feedback. Teachers can use this rubric to help kids notice when they are collaborating well, and where they might need to improve. Evidence of good collaboration can be documented in a digital portfolio, with teachers, students and even parents adding feedback. But at no point is the child graded on collaboration, or told they are in the bottom quintile.

Willis, from Susquehanna, worries that universities and employers say they want the data, but might not know how to use it. “The data is only as good as your capacity to interpret it,” she notes. And schools will need staff to make sure the skills-based experiences are rigorous, evidence-based and meaningful and not another faddish flyby, of which there are so many in education. Willis’ district put in place a service learning requirement and quickly realized it needed a full time person to manage those experiences. “This is going to require a lot of time to really, like unravel a centuries old industrial era model of learning. It’s a huge shift in terms of our paradigm,” she said.

Rather than promoting equity it could undermine it by creating a two tier system—or more of one— in which wealthy kids take APs and SATs and pursue an academic route, while low income kids follow a skills-based route that is deemed less rigorous. “If you do performance- based assessments, there will be a faction of people that say, ‘Oh, you’re lowering the standards and just getting kids through? ‘It’s not the lowering of standards, just providing choice on how to meet those standards,” says Soler.

What the two organizations develop will clearly be more important than their recognition that a shift is needed. Many legacy systems “have been really problematic, often inhibiting learning and individual needs, strengths and growth,” argues Jennifer Groff, Founder and CEO pf Learning Futures Global, which helps schools and education systems re-engineer learning around outcomes they identify rather than ones they default to. “Getting that right, so it aligns with how we know people learn and develop mastery is critical.”

One innovation is that ETS and Carnegie are explicitly including parents, students, teachers and policy makers in developing the new assessments. That will be messy but potentially valuable. It will uncover what parents and educators want, informing the kind of system that needs to be built. Knowles is reassured that there is broad consensus for this, in spite of massive polarization. The right wants a focus on skills for jobs; the left for equity. The route, he argues, can be the same.

Parents may be the biggest road block. Often in education reform they are ignored and they fight changes in familiar signals such as grades and GPAs. Willis saw this when they started to talk about competency based education. “They just want to know that their child is valedictorian, or that my child is salutatory. And what is their class rank? Are they going to be able to get into college They are fully in support of you maintaining the structure that they themselves had when they were in school.”

But the risk of continuing with what’s not working may be greater than trying to adapt and reflect what the science of learning highlights: overweighting one-time, high stakes tests are is not a great way to unleash human potential.