Growing up in the Soviet Union in the 1960s and ’70s, Mikhail Gershkovich and Ella Milman learned to be careful. Children knew not to repeat what their parents said in their kitchens.

Mikhail recalls his father, who grew up under Stalin, offering a piece of advice: If you’re going to tell a political joke, “make sure there are no witnesses.”

Mikhail and Ella both emigrated to the U.S. in 1979, seeking to escape rising antisemitism and life under Soviet rule. They met in Brooklyn in the 1980s, got married, and raised an American family in suburban New Jersey. Their daughter Danielle took swimming and gymnastics. Their son Evan played soccer. “Here, we can relax,” says Mikhail. “Just find yourself. Decide what you want to do.”

Evan Gershkovich decided he wanted to be a journalist, a calling that took him back to his parents’ homeland. He had grown up speaking Russian, and wanted to use his familiarity with the language and culture to pursue his career. He worked as a reporter for the Moscow Times, Agence France-Presse, and the Wall Street Journal. When Ella worried about him writing articles critical of the Russian government or economy, her son explained that he was an “accredited journalist,” his mother recalls, repeating the phrase as though it were a magic shield.

But it wasn’t. On March 29, 2023, Evan Gershkovich was detained by Russian security forces while meeting a source at a restaurant in Yekaterinburg, an industrial city about a thousand miles east of Moscow. He has been a political prisoner in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison for nearly a year, the first American journalist to be accused of espionage in Russia since the Cold War.

Gershkovich is not a spy. He has never worked for the U.S. government. The White House calls the charges against him “ridiculous” and classifies Gershkovich as “wrongfully detained.”

“Russia has taken Americans hostage before, but an accredited journalist is another level in terms of what it says about the country’s relationship with the West, or America specifically,” says Gershkovich’s friend Polina Ivanova, who covers Russia for the Financial Times. His arrest was a “watershed moment” that represents Russia’s disregard for international norms, Ivanova adds. “It wasn’t that Evan’s work had changed. It was that Russia changed.”

For his immigrant family, Gershkovich’s detention shattered a belief that their son could chase his American dream in the country of his heritage. Perhaps the cruelest irony is that Gershkovich loved Russian culture; his goal as a reporter, family and friends say, was to depict in its full complexity a country that is often reduced to caricature. Instead Gershkovich is trapped in limbo. So are his parents. Forty years after they fled Soviet Russia, their only son has become a political pawn in a new Cold War, a human bargaining chip for Vladimir Putin as relations between the two countries cratered with the invasion of Ukraine.

On Feb. 20, Russian courts rejected the latest appeal filed by Gershkovich’s lawyers. He is set to remain imprisoned through at least March 30, a year since he was originally detained. While the Biden Administration calls his release a “top priority,” negotiations to free him have not made progress. Late last year, the U.S. presented a “significant proposal” to free Gershkovich and former U.S. Marine Paul Whelan, who has been held by Russia since 2018 and is currently serving a 16-year sentence in a penal colony on spurious charges of espionage, according to State Department spokesman Matt Miller. The Russians turned it down.

Putin has expressed openness to a potential prisoner swap. The U.S. and Russia completed one in December 2022, exchanging the American basketball star Brittney Griner, who was detained in Russia for drug possession, for the notorious arms dealer Viktor Bout. But there are significant obstacles to consummating a deal now, according to two U.S. officials familiar with the talks.

Those officials say the U.S. isn’t holding any prisoners Russia values highly enough to exchange for Gershkovich and Whelan. Putin has sought the release of the convicted Russian hit man Vadim Krasikov, who is serving a life sentence in Germany for assassinating a Georgian dissident of Chechen ethnicity in a Berlin park in 2019. But U.S. officials say Germany is not currently willing to include Krasikov in a swap.

The suspicious death of Russian dissident Alexei Navalny in a Siberian penal colony presents an additional complication. Allies of Navalny alleged on Feb. 26 that he was killed before he could be released in a deal that would have involved Gershkovich and Krasikov. A U.S. official familiar with the negotiations tells TIME that no formal proposal for a three-way prisoner swap had been extended involving Navalny and U.S. citizens, but that in “nascent” conversations, Germany seemed more willing to release Krasikov while Navalny was alive. Now that Navalny is dead, “Germany has very much cooled to the idea,” the official says.

Read More: Why the Kremlin Tried to Obstruct Alexei Navalny’s Funeral

The political context also contributes to the challenge. Putin may be reluctant to make a deal before the U.S. election in November, because he prefers that President Joe Biden lose to Donald Trump and is wary of making an exchange that might be seen as a victory for Biden, people familiar with the talks believe. “They’re not looking to hand the Administration any wins,” says a U.S. official.

The Administration says that Gershkovich’s release is a top priority. “Not a day goes by without intensive efforts from the State Department and others across the U.S. government to reunite Evan and Paul with their families,” Roger Carstens, the special presidential envoy for hostage affairs, said in a statement to TIME.

Gershkovich’s family and friends have not given up hope. “Pessimism is a quality common in Russia,” Milman says as she sits in Danielle’s Philadelphia apartment. The walls are decorated with illustrations Evan gifted Danielle over the years: a cat wearing a tie, a devil playing a cello, a joke sign from a cemetery that says Sorry, we’re dead. “It’s the optimism that carries me on,” Milman says. “If you accept the negative, it’s like the game is over.”

Gershkovich arrived in Russia in 2017. Three years out of college, he had landed a job at the Moscow Times, an independent online newspaper that publishes in both English and Russian. He formed a close-knit group of journalist friends who lived in the same Moscow neighborhood, Chistye Prudy. They hung out at hipster cafés, art exhibitions, and concerts. They joined Russian soccer teams. They rented a dacha outside the city, where they spent summers grilling and winters cross-country skiing. The job was endlessly interesting. “Russia was a place where journalists had freedom to maneuver and freedom to do lots of good work,” says Ivanova. “It was this exciting place to discover that he had lots of connections to and cultural knowledge about.”

When Gershkovich’s parents arrived for a visit in 2018, Milman was struck by the country’s transformation. The family walked through the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and sampled Evan’s café recommendations in a “new, shiny Moscow,” as Milman describes it. Evan “was excited to show them the Moscow he had come to love,” says his close friend Pjotr Sauer.

Putin’s Russia has always been a dangerous place for reporters. At least 39 journalists and media workers have been murdered in Russia since 1992, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists. But Gershkovich was an American citizen with formal press accreditation from the Russian government. He felt his own safety risks were minimal. “Every year it was becoming more authoritarian,” says Sauer. “But you still felt like you could talk to opposition leaders. There were protests. You could travel.”

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, those freedoms were curtailed. There were new laws that inhibited journalists’ movements, and new rules about what could and couldn’t be said. Many journalists left; the ones who didn’t were constantly looking over their shoulders. Gershkovich himself moved to London, but he returned to report as often as he could. “Reporting on Russia is now also a regular practice of watching people you know get locked away for years,” Gershkovich tweeted in July 2022. He told friends he had occasionally been followed.

Read More: As Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion Enters Its Third Year, Optimism for Ukraine Sinks

If anything, the exodus of colleagues made him more committed to his work. “He saw it as his mission to be back in Moscow,” says Sauer. “He felt like he had a responsibility to tell this story.”

Gershkovich was not in the habit of keeping his parents apprised of his whereabouts at all times. When he called on March 27, 2023, his mother had thought he was in London. “He called me to reassure me that everything was OK,” Milman recalls. “He said, ‘I’m delaying going back; I want to finish something.’” Milman was vaguely unsettled, but she trusted him.

Two days later, on the morning of March 29, Gershkovich exchanged texts with Sauer about Arsenal, their favorite soccer team. They made plans to meet up in Berlin for Easter. There was no hint of alarm. “We couldn’t imagine that he would be taken off the street and charged with espionage,” says Sauer. “It had never happened in modern Russia. It seemed out of the range of possibility.”

That afternoon, Gershkovich was detained by Russia’s Federal Security Services (FSB) at a steak house in Yekaterinburg. He was escorted out of the restaurant with his hood pulled over his head.

Emma Tucker, the editor in chief of the Wall Street Journal, woke to her phone ringing shortly before 4 a.m. and knew the news was bad. Liz Harris, the Journal’s managing editor, was calling. There were unconfirmed reports online that the FSB had detained Gershkovich on suspicion of espionage, Harris told Tucker.

Tucker had braced for this. The previous day, Harris had notified her that Gershkovich had missed his check-in on the Dow Jones global security system, a standard procedure on dangerous reporting assignments. At first, Tucker took the news in stride. His phone could have died; there was no need to panic. But later that afternoon, Harris said that Gershkovich had missed a second check-in. Editors were worried.

After the second missed check-in, Tucker called Paul Beckett, then the Journal’s Washington bureau chief. Beckett was at a dinner in D.C. The appetizers had just been served. He walked out into the courtyard to take the call from his new boss. “Paul,” Tucker said in her clipped British accent, “Evan Gershkovich has gone missing.”

At that point, missing simply meant that editors hadn’t heard from him. But Beckett began reaching out to national-security contacts. By a little before 8 p.m., he had contacted a top aide to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley, called the State Department’s press office, and emailed Deputy National Security Adviser Jon Finer. Finer called back within the hour, assuring Beckett that the Administration was taking the situation seriously. Around 10:30 that night, Secretary of State Antony Blinken called Beckett and Tucker.

The editors held out hope. “I kept waiting for the call saying, ‘OK, he was roughed up by the security services, but he’s out,” says Tucker. “And that call just didn’t come.” Instead came an FSB press release announcing that Gershkovich had been arrested on espionage charges. It was a “body blow,” says Almar Latour, CEO of Dow Jones, which publishes the Journal. “It confirmed our worst fears.” With the spurious allegations of espionage, “the stakes went up,” Latour adds, “and the level of complexity immediately became much greater.”

Read More: Russia’s Arrest of a Wall Street Journal Reporter Has More to Do With Geopolitics Than Espionage

Tucker had been the top editor of the paper for only a few weeks. She had just moved from London to take the job, and most of her furniture had not yet been delivered. She sat on a stool at her kitchen counter and got on a call with a few senior editors. Together they drafted a note to the newsroom relaying what they knew.

Beckett spent the next 36 hours wrangling government support. “It was important to us that the message come from the White House as quickly as possible that he is not a spy,” Beckett says. Tucker embarked on a media tour. “Someone along the way gave us the advice that ‘There are moments to be loud and moments to be quiet, and this is a moment to be loud,’” Beckett says. “That became a bit of a mantra.”

The legal team at Dow Jones focused on getting Gershkovich the right representation—a challenge complicated by the withdrawal of most Western law firms from Russia. One hurdle was finding a good lawyer who also wasn’t “politically aligned in one way or another,” recalls Jay Conti, Dow Jones’ general counsel. “You don’t want that to be a signal.”

When Harris called Gershkovich’s family to tell them Evan had gone missing, his mother was the one who answered the phone. “I’ve never experienced anything like it,” Milman says. “It’s a shock.” Harris promised to call Milman every hour, whether there was news or not, and to update her as soon as she heard anything. “Time stops,” Mikhail recalls. “It’s hard to breathe.”

Tucker and Harris went to Philadelphia to meet the Gershkovich family for lunch at a tapas restaurant. The meeting made the family feel that “we were not alone,” Milman says. “We were supported.” In recent months, the family has been in almost daily contact with the Journal. They hear from Carstens, the special envoy for hostage affairs, roughly every week, whether or not there are major updates in the case. Usually, there aren’t.

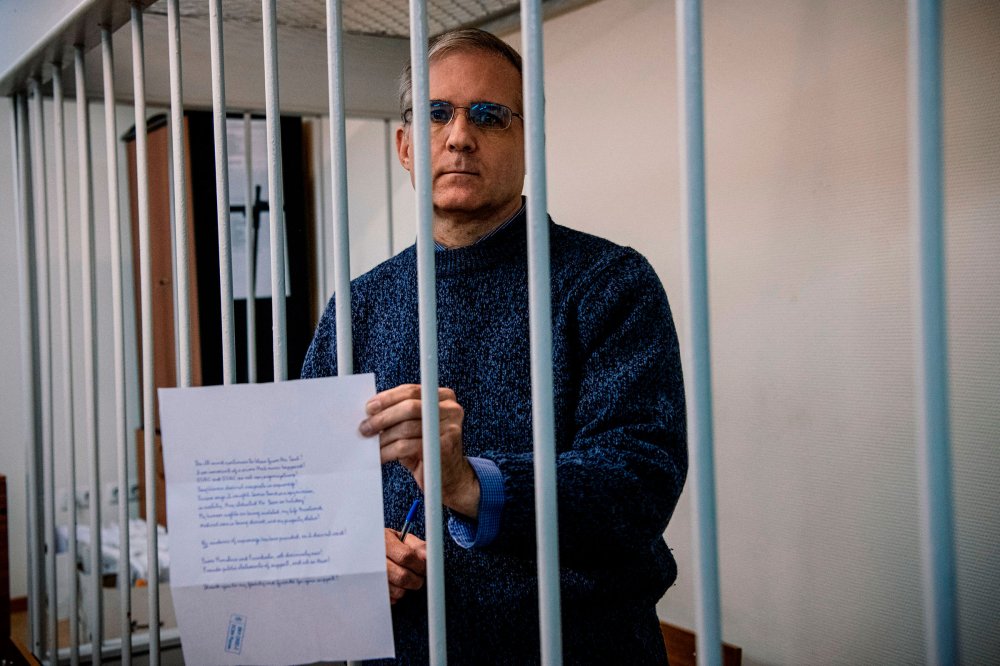

Milman has seen her son twice since his arrest. It’s the cages that stick out in her mind. In late May 2023, when his parents visited him in Lefortovo, Evan was in a metal cage. The second time, that June, they came to one of his pretrial appearances in a Moscow courtroom. This time the cage was glass. “We walked in and noticed a huge smile,” Milman recalls. “We went and stood next to him, and immediately, Evan was already talking and joking.” The family had a brief conversation through the glass. “We were laughing,” Milman says. “Russians don’t expect laughter in a court. Crying—that’s what they expect. But we were laughing.”

Gershkovich writes his family upbeat letters about once a week. Over correspondence, he plays long-distance chess with his father and trades jokes with his mother. Danielle sends him gossip about family members and celebrities, and does tarot card readings for him. Gershkovich spends time answering the mail he receives, which is translated into Russian and passes through prison censors. He reads Russian literature. Someone sent him a book of exercises you can perform in a small space using your own body weight. He tries to maintain his mental health. His primary focus, says his family, seems to be reassuring them from afar.

U.S. Ambassador to Russia Lynne Tracy, who has visited Gershkovich eight times since his detainment, says she’s been impressed by his “amazing resilience of spirit.” Even behind bars, Tracy says, Gershkovich has been keeping up with U.S. current events. “Whatever topic I’m bringing,” she adds, “I always have to have a little more information for the follow-up question that I know I’m going to get.”

Lefortovo is notorious for conditions that can border on psychological torture. Most prisoners are kept in isolation so complete that guards make a special clicking sound as they escort prisoners through the hallways to warn prisoners from interacting in passing. “Physically it’s fine—you know that you cannot be attacked by anyone. It’s about psychology,” says Andrei Soldatov, a Russian journalist who has been questioned at Lefortovo. The interrogations are excruciating: long, slow conversations, in which the questioners constantly reformulate answers in bureaucratic language in order to trick prisoners into incriminating themselves.

For Gershkovich’s family, friends, and colleagues, the ordeal has been a lesson in the agonizing dynamics of international hostage negotiations. The Journal has launched a task force and a media campaign called #IStandWithEvan. The arrest was a “signal” from Russia: “‘Welcome to the world of dictators, where the rules are different,’” Latour says. “We have to make sure that this behavior is seen as unacceptable on the global stage.”

Russian secrecy laws governing espionage charges make it difficult for either the attorneys or diplomats to get clear updates on the legal substance of his case. And there has been little apparent progress on the diplomatic front.

“What we’re seeing is the Russian government treating innocent people as political pawns,” Ambassador Tracy says. While she won’t comment on the status of ongoing negotiations, she notes that the Russians are “transactional” in their approach. “This is hostage taking to trade for something.”

The extension of Gershkovich’s pretrial detention through the end of March creates an added complication. Until the trial, it won’t be clear exactly what alleged evidence Russia is planning to bring against him. U.S. officials familiar with the situation say they’re bracing for the possibility that Gershkovich may face a fate similar to Whelan’s: a secretive sham trial, followed by sentencing to a penal colony.

In a rare interview in early February, Putin suggested to Tucker Carlson that he was open to releasing Gershkovich in a prisoner swap and said that Russia is in “ongoing dialogue” with the U.S. “I do not rule out that the person you are referring to, Mr. Gershkovich, may return to his motherland,” Putin said. But Putin also appeared to allude to Krasikov, the Russian hit man imprisoned in Germany. Krasikov is “not currently available to us,” says a U.S. official familiar with the negotiations, who notes, in addition to the death of Navalny, the heinous nature of Krasikov’s crime. The U.S. is negotiating with allied countries in an attempt to cobble together other offers, adds the official. Biden Administration officials fear Putin may slow-walk negotiations during a presidential election year. It wasn’t a coincidence, one says, that Griner was released only after the 2022 midterms. “They’re trying to maximize pain and political pressure,” the official says.

In the meantime, Gershkovich sits in Lefortovo, writing to his family and friends, carrying on his active social life from prison. He keeps track of his friends’ birthdays, and writes others with specific instructions for giving them gifts—which flowers to buy and how to deliver them. When Ivanova had a birthday in late January, another friend urgently requested to meet up with her, then handed her a bouquet of tulips. The note said, “From your friend who couldn’t write the card himself.” —With reporting by Leslie Dickstein and Julia Zorthian