On March 3, 2020, just before lunchtime in Washington, D.C., Stephen Ryan sent someone at the U.S. Treasury department a thank-you note with a curious detail.

The chief operating officer and co-founder of cryptocurrency sleuthing firm CipherTrace, Ryan was one of 16 executives who attended an industry summit the day before with then-Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. Along with his gratitude for the meeting, Ryan attached a slide deck that laid out CipherTrace’s strategy for demystifing crypto wallets. Among those methods: “honey pots.”

This article is part of CoinDesk’s Privacy Week series.

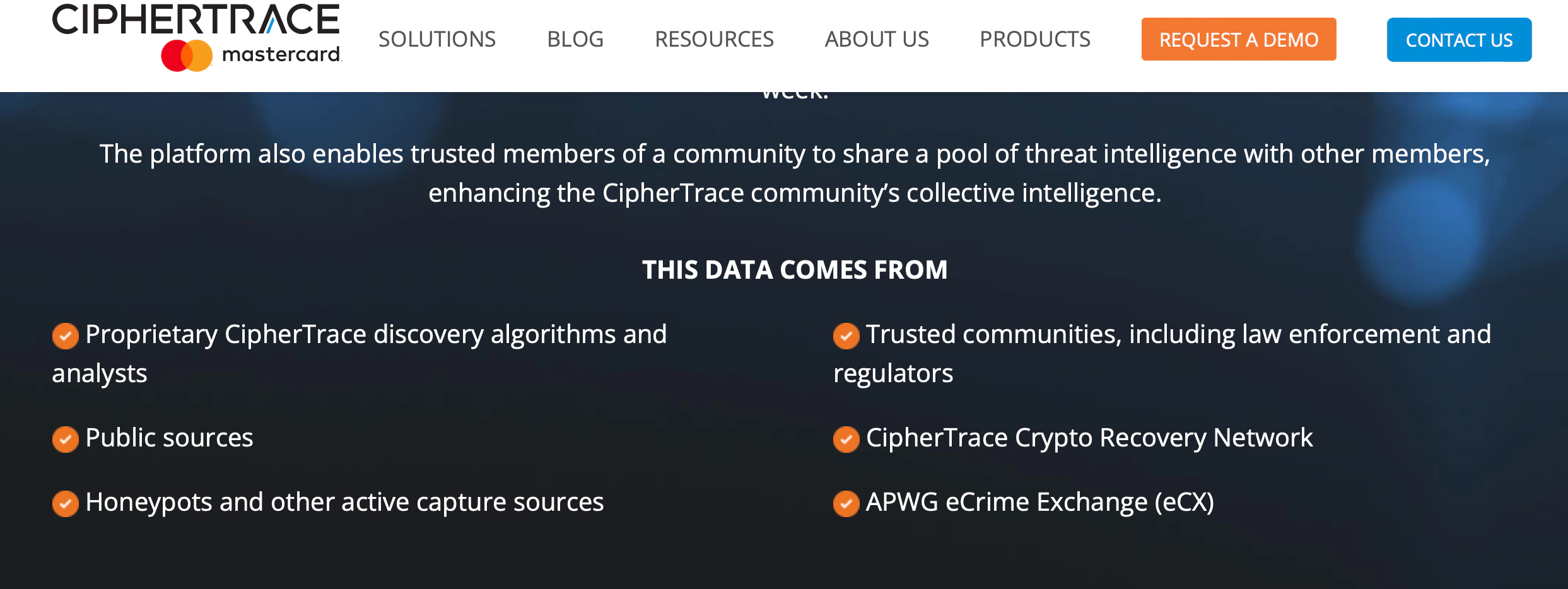

Ryan’s note was part of a 250-page trove of Mnuchin’s emails obtained by CoinDesk through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. Portions of his slide deck closely resemble CipherTrace’s public promotional materials. Those, too, have referenced “honeypots,” or the rhyming “crypto money pots,” since at least 2018.

What did CipherTrace mean by these terms? The cybersecurity community uses the phrase “honey pot” to describe a decoy target that collects intelligence on unsuspecting attackers. In other words: a trap.

CipherTrace, which payments giant Mastercard purchased last fall for an undisclosed price, is part of a cottage industry that monitors the $14 billion-a-year crossroads of cryptocurrency and crime. Sifting through millions of daily transactions recorded on blockchains, or public ledgers, firms like Chainalysis, TRM Labs and Elliptic search for red flags and illicit movements, labeling suspect addresses as they go.

The companies cast their service as essential to normalizing crypto and stamping out crime. Detractors lambast these tracing firms as on-chain narcs, even though they are primarily working with public information.

CipherTrace wouldn’t be the first company in this niche to set snares in hopes of capturing information that can’t be found on-chain. Chainalysis, the leading crypto tracing vendor, has for years owned a wallet explorer site that captures visitors’ IP addresses and links them to the blockchain addresses they looked up. The company acknowledged this practice only last October, the month after CoinDesk published an article drawing attention to it.

More than half a dozen cryptocurrency industry veterans told CoinDesk they had no idea what CipherTrace meant by “honeypots.” In a statement provided to CoinDesk, the Los Gatos, Calif.-based company gave the basic computer security definition without explaining what it meant in the context of blockchain analysis.

“A ‘crypto money pot’ or ‘honeypot’ is a security term referring to a mechanism that creates a virtual trap to lure would-be-attackers,” CipherTrace said, adding that the documents mentioning these tactics are old. “CipherTrace does not use ‘crypto money pots” anymore, it said (although the company’s website touted both money and honey pots as of Thursday).

CoinDesk asked CipherTrace: “Does your firm collect IP address data for the purposes of linking them to wallet addresses?”

A CipherTrace representative responded: “As a privacy-focused company, CipherTrace does not map IP data to private individuals.”

She did not answer CoinDesk’s question: whether CipherTrace maps IPs to wallets. CoinDesk asked a second time if CipherTrace maps IP addresses to wallet addresses. CipherTrace did not respond.

Such caginess “is a frequent issue in the privacy space, when we talk about network identifiers like IP addresses.,” said Sean O’Brien, a cybersecurity researcher. “Companies try to distance themselves from what you would traditionally call personally identifiable information by saying IP addresses are something else. In fact, they’re incredibly useful for identifying households, businesses and individuals.”

For example, “if you need to investigate a Bitcoin transaction related to a suspected cybercrime, IP addresses are exactly the kind of information you’d be looking for,” O’Brien said. “The earliest cases involving law enforcement and the internet hinge on IP addresses as evidence, for good reason. And, they’re just as useful to harass and stalk people as they are to prosecute them.”

Following the money

Tracing companies have long been a major if underrecognized force in crypto’s institutional march. Fighting back against a tired perception that bitcoin is primarily a criminal finance tool, they parse the data to pinpoint the meager share that actually is.

Chainalysis recently estimated that 0.15% of crypto transactions in 2021 were illicit – by far the smallest percentage on record. (“Illicit” wallets amassed a record-high $14 billion last year, a seemingly paradoxical stat that Chainalysis attributed to crypto’s booming growth.)

CipherTrace says its mission is to “grow the cryptocurrency economy by making it trusted by governments, safe for mass adoption, and protecting financial institutions from crypto laundering risks.”

Taken from the presentation shared with Treasury, that description would likely be shared by every competing firm. It gets at the heart of detractors’ concerns. Privacy maximalists believe that Bitcoin’s radically transparent but pseudonymous nature ought to flow independent of the state, and they see these companies’ work as a betrayal of that ideal.

“It’s kind of an invasion of privacy of users, the same way that you might complain about centralized web analytics companies that are collecting IP addresses and putting cookies on people’s computers and tracking them from site to site,” said John Light, a longtime crypto educator, writer, podcaster and event organizer.

On-chain analytics is, at its core, an attribution race.

In cybersecurity circles, attribution means identifying the perpetrators of a hack. In the crypto context, it refers specifically to blockchain sleuths’ practice of linking pseudonymous wallet addresses to identifiable actors. These actors could be licensed crypto exchanges or custodians; ransomware attackers; darknet marketplaces; or sanctioned individuals or entities.

For example: Anyone with an internet connection can see that, say, wallet abc123 transferred 0.5 BTC to zxy987; this information is rather useless on its own. But a tracer database might document that the U.S. Office of Foreign Assets Control has identified zxy987 as belonging to a sanctioned African warlord. Or it could show that abc123’s bitcoin was stolen from an exchange.

That’s valuable information for exchanges that want to cut out illicit activity, for users who want to keep their coins clean, for governments who want to follow the money. It comes together through rigorous attribution.

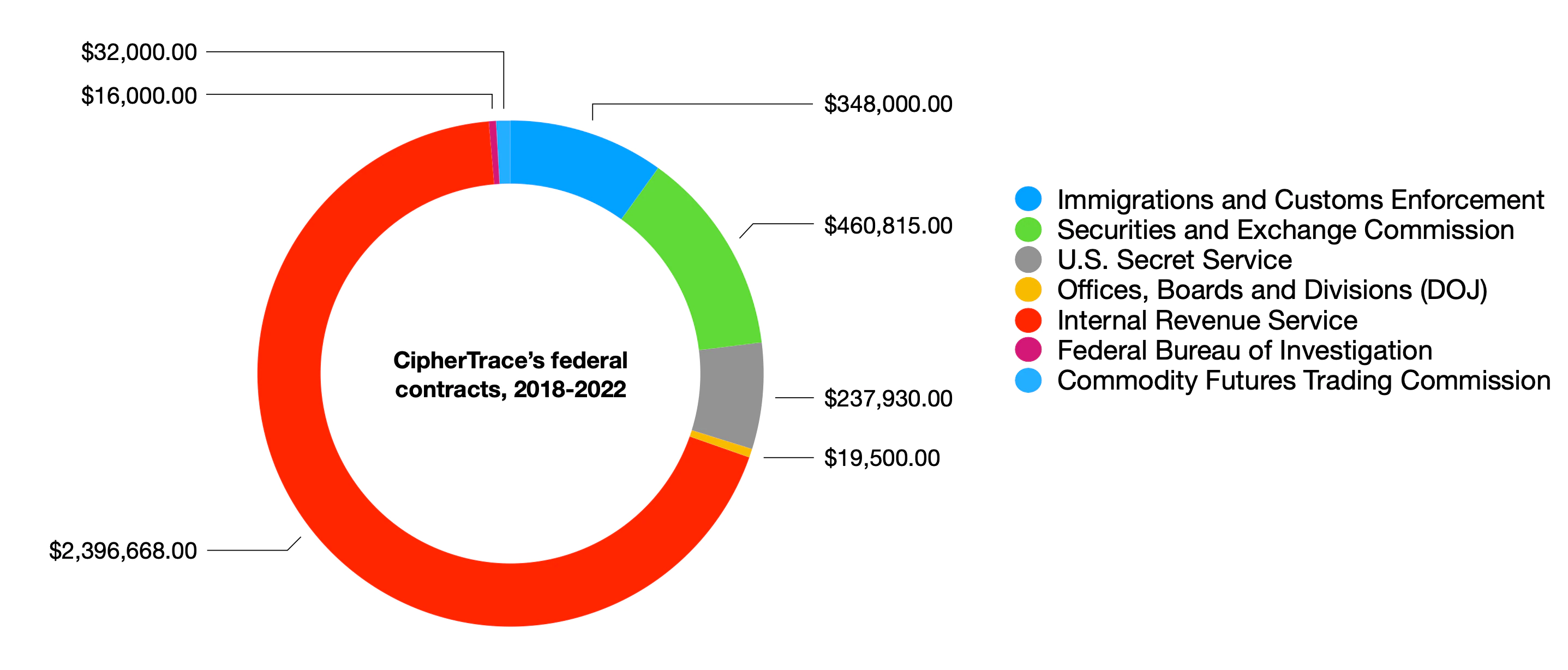

With potentially millions of dollars in investigatory contracts up for grabs, these companies have an acute need to mine novel attribution data. CipherTrace, for example, has scored 20 contracts with federal agencies, worth up to $3.5 million, since 2018, the most recent being an expert witness job, according to public records.

In an industry that rewards builders of nuanced, detailed, attribution datasets – and a field where criminals are hungry for intelligence to help them escape notice – guarding the attribution secret sauce is paramount, two longtime practitioners said.

Nevertheless, in his email to the Treasury, Ryan offered a taste “of how cryptocurrency attribution is achieved.” Honeypots were listed as one of the “active” strategies in the slide deck.

Chainalysis: Blockchain attribution ace

CipherTrace’s biggest competitor began operating its own novel technique three years before.

Founded in 2014 and valued last June at $4.2 billion, Chainalysis is the tracing industry’s big kahuna. It’s racked up tens of millions of dollars in federal contracts selling software that visualizes on-chain activity. While anyone with an internet connection can self-sift through public blockchain records, you’d need a little help to make sense of what you find down the rabbit hole.

But the tracer’s true business ace is its attribution dataset, three industry insiders said. No other company has amassed a trove of wallet data as detailed as Chainalysis’, the sources said.

That’s partly because no other tracer has as massive a business footprint. Chainalysis provides tracing software to 500 “virtual asset service providers,” or VASPs, as regulators call them. It’s a mutually beneficial relationship: The businesses get powerful crypto compliance tools, and Chainalysis adds their wallet addresses to its global database. It does not, however, ask clients for data on their customers.

“We can’t speak for all other vendors. It’s possible other vendors may ask for more information. But Chainalysis is concerned only with service-level transaction data,” the company explained in a 2019 blog post. In other words, it identifies only businesses that it knows control wallets, not people.

But that wasn’t the whole story, and Chainalysis’ customers, and public information about wallets, were not the firm’s only sources of intel.

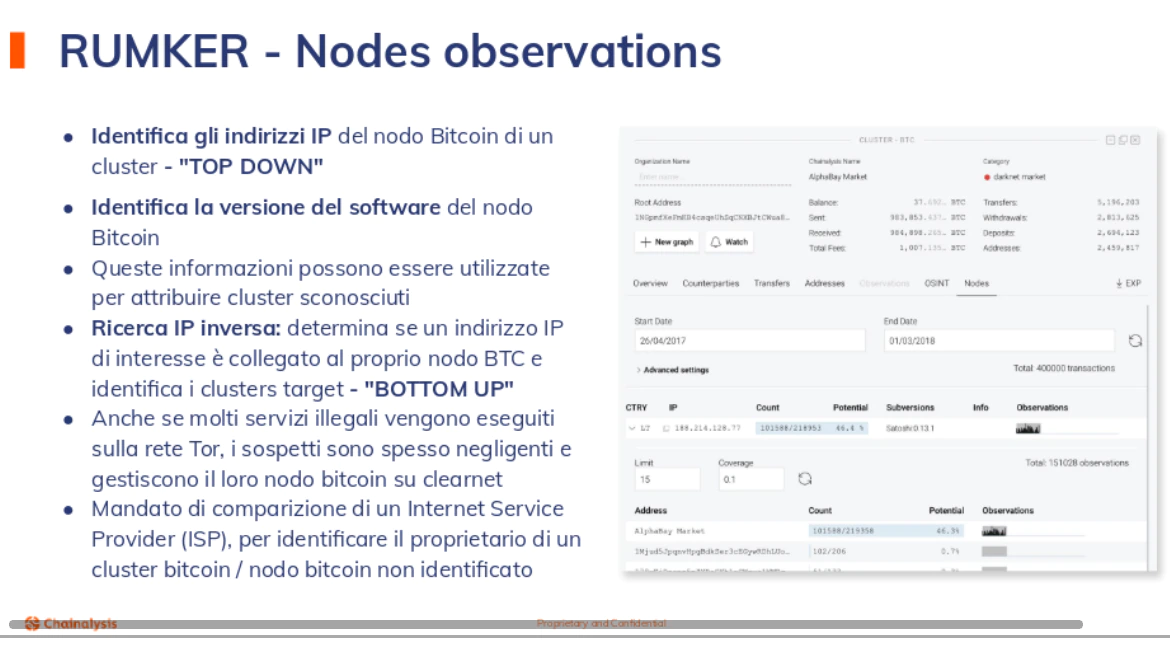

In an undated slideshow for Italian police that was leaked last September, a Chainalysis sales team described how the company’s vast network of Bitcoin and Electrum wallet nodes capture valuable user data such as IP addresses from connecting wallets. This helped investigators follow meaningful criminal leads, the presentation said.

The slideshow also shed new light on walletexplorer.com, a popular Bitcoin block explorer run by Chainalysis since 2015. According to the documents, which CoinDesk verified were authentic, the website “scrapes” suspicious users’ IP addresses, linking their internet footprint with their wallet address. This dataset has provided “meaningful leads” for law enforcement.

”It was never a secret that Chainalysis owned and operated walletexplorer.com; since 2015 there has been a statement at the bottom of the homepage that the author of the site works at Chainalysis as an analyst and programmer,” a company spokesperson told CoinDesk.

An open secret, perhaps, but hardly an open book. Chainalysis seldom brought attention to the fact that walletexplorer.com was funneling user data to its other business lines.

Weeks after CoinDesk reported on walletexplorer.com, the website adopted a privacy disclosure page that spelled out, for the first time, how its data trove wends its way into the Chainalysis product line.

“We share Blockchain Information and Visitor Information with our other Chainalysis business lines to help us deliver and improve those services. For example, other Chainalysis business lines may be able to use the information we provide to better connect one Bitcoin Wallet Address to another Bitcoin Wallet Address,” the Oct. 14-dated policy said.

“We more recently added a privacy notice to provide more information about how Chainalysis internally uses information collected from the walletexplorer.com website to help improve our services,” the spokesperson said.

Nothing personal?

While it remains unclear exactly what CipherTrace’s honeypots do, the word evokes a system that purports to do one thing while triggering something else. A wallet owner engaging with a “honeypot” would be definitionally oblivious to the service’s ulterior motives.

Chainalysis, CipherTrace and Elliptic have all previously stated that they do not seek to tie individuals to wallets. Their business is in helping governments investigate crypto crime and keeping exchanges compliant.

Outing individuals isn’t a part of that equation. These companies simply follow the money, they say.

“The blockchain intelligence we provide links crypto transactions to real-world entities such as exchanges, darknet marketplaces and sanctioned entities,” Ari Redbord, head of legal and government affairs for TRM Labs, told CoinDesk.

“This intelligence allows a crypto exchange to be alerted if, for example, it processes a transaction involving an address that has previously been used for terrorist financing,” he said. “The same applies for transactions involved in hacks, ransomware, rug pulls and other attacks that harm crypto investors and users.”

But “we do not attribute transactions to individuals,” Redbord said of TRM Labs.

Similarly, CipherTrace’s representative said it “does not attribute wallet data to private individuals, with an exception for sanctioned entities.” It’s done that prolifically, boasting in one 2019 blog post of attributing 72,000 Iranian IP addresses to 4.5 million wallets.

Whether CipherTrace attributes IP addresses to other wallets remains an open question. Top company brass say they don’t maintain “personally identifiable information,” just “business identifiable information.”

“CipherTrace does not maintain PII, we maintain BII” CipherTrace CEO Dave Jevans said in an interview last June.

“We understand, for example, what addresses belong to what exchange,” he said. “But we don’t track individual information that it’s you at this address; that’s not our business. We don’t want to do that. We’ll figure out where the money comes in, where the money goes out and then it’s up to the courts and law enforcement,” to do the rest.

As O’Brien, the cybersecurity researcher, noted, CipherTrace’s definition of personally identifiable information appears to exclude IP addresses – along with physical locations, according to one of the company’s own blog posts: