For military servicemen during World War II, the sight of a blue discharge paper was a sentence for struggle. The color, indicating a dishonorable discharge from the military during a time long before “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” and when homosexuality was classified as a mental illness, not only formally outed people to their friends and family, but also cut their access to military benefits, setting them up for prejudice in the workforce and beyond.

Of the more than 9,000 servicemen and women who received a blue discharge during World War II due to the ban on queer service members—though there were thousands of others who received dishonorable discharges for other reasons—many decided to settle in San Francisco, cementing the city as an LGBTQ+ hub—a legacy that originally stemmed from the town’s reputation as a hotbed for sex and gender nonconformity in the 1800s. “Ever since the Gold Rush, there was already a kind of queer world in the city, but certainly, the military role in World War II built upon that world,” Steve Estes, a history professor at Sonoma State University, tells TIME.

Many were attracted to the city because it provided them with a sense of freedom from the judgment they’d likely receive at home due to their sexuality. It was also easily accessible, serving as a major port of disembarkation for more than a million individuals throughout the war. “Homosexuals who couldn’t hope to pass for straight set up their own small businesses that created a group of openly gay people [in San Francisco] with an economic base to sustain the possibilities of a movement here,” says Gerard Koskovich, a founding member of the GLBT Historical Society.

The city’s long-standing history earned it the status of the “gay capital” of the U.S. in a 1964 LIFE Magazine issue. San Francisco was also one of the first cities to issue same-sex marriage licenses in 2004—though the licenses were not legally binding at the time.

The number of queer-identifying individuals in San Francisco’s gay neighborhoods has diminished over time, in part due to a trend of declining affordable housing units that has also been seen in other corners across the U.S. Still, San Francisco remains a mecca of LGBTQ+ history and culture.

How the military played a role

The roots of San Francisco’s LGBTQ+ community came following the Gold Rush in the late 1840s. “It went from being a small village of about 850 people to being a city with 50,000 residents, almost all of them young, single men who didn’t fit in back home and decided to try their luck in San Francisco,” says Koskovich. Like other port cities, the community attracted “vice businesses,” including gambling and prostitution.

But San Francisco’s role as a port of embarkation for the Pacific Ocean Theater during World War II also played a prominent role. More than 1.5 million soldiers passed through the city in the 1940s, attracting many to the Californian community. During that period and long after, the U.S. military conducted scrutinous screening of the sexual orientation of its troops and staff.

For some Americans, it was the first time they heard the word homosexual and understood what that term meant. Some historians say the draft process raised greater social consciousness about sexual identities that were outside of the norm. Some LGBTQ+-identifying troops found a “homosocial world in the military,” Estes says, which was not necessarily accepting but was “a world away” from the towns where they came.

The U.S. military had strict policies regarding service members that were attracted to the same-sex, forcing many to lie about their sexual orientation to serve. “One of the arguments against letting gay people in the military is that they could be security risks,” says Estes, who says that military leaders feared that queer duty members could be blackmailed into revealing U.S. secrets in exchange for staying silent about their orientation. “It was this classic Catch-22. You’re not allowed to be in the military because you’re gay. And you’re not allowed to be gay because you’re a security risk, because you’re not allowed to be in the military.”

Many LGBTQ+ serving individuals sought refuge in San Francisco because the blue paper served as a stain on their employment and housing opportunities elsewhere. “No point in going back to your small town in the middle of nowhere in the Midwest to try to get a job with that kind of discharge. The first thing any employer asked for was your honorable discharge from your military service,” says Koskovich.

At the same time, San Francisco’s own population was also largely depopulating as it deindustrialized. While the quality of its schools, jobs, and neighborhoods decreased, a new set of residents found their way to the city. “It was a good place for this new population of young, largely gay men fleeing persecution elsewhere in the United States to come to what was really a kind of declining city. [They] were willing to live here even if the schools were poor, [or] if the neighborhoods weren’t really safe. These young men didn’t have families, they didn’t have kids. They weren’t worried about that. They wanted to have liberty, and this was a place for them to get it,” Koskovich says. Still, there were several actors—including the military’s San Francisco Moral Drive—that frequently raided gay spaces, which were in that time limited to bars and nightclubs.

By the 1950s, discrimination against LGBTQ+ individuals in the workforce led to the Lavender Scare, which removed queer individuals from roles within the federal government during the Cold War. Queer individuals, including veterans and other residents, moved to mobilize. Two leading organizations—the Daughters of Bilitis, the first national lesbian political organization, and Mattachine Society, a national gay-rights organization—were founded or had their headquarters in San Francisco in the 1950s. Their emergence was part of a growing movement towards liberation and against conventional society that was promoted by the Beatniks. “The Beat generation’s desire for sexual liberation fostered increasing acceptance towards homosexuality, and as the movement grew in popularity, its members helped to establish many gay social and political groups in San Francisco,” the California Migration Museum says.

Soon after, the LGBTQ+ community became even stronger. “In the early 1960s in some cities, notably in San Francisco, due to changes in society, politics, and police practices, you began to see what we would think of as an actual neighborhood emerge,” says Koskovich, mentioning the emergence of the Castro District. “There were bars, or nightclubs, or cabarets catering to LGBTQ+ people, but also daytime businesses like restaurants, or clothing shops, or record stores, or ultimately services providers like doctors and lawyers and so on.”

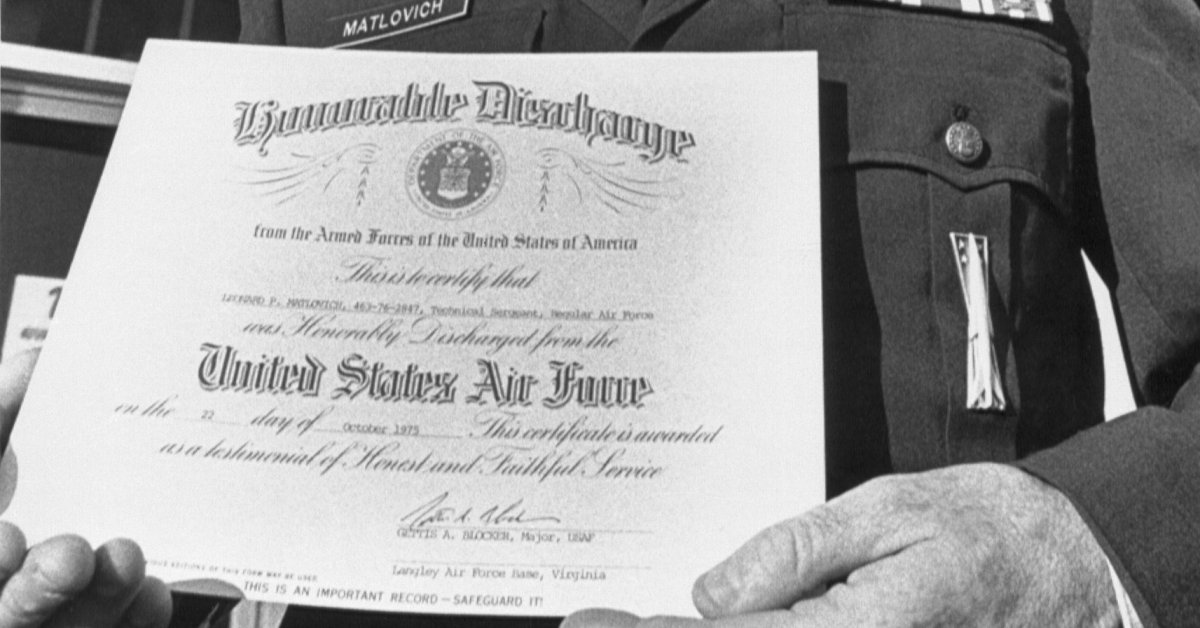

Leading figures for the queer liberation movement also appeared. José Sarria, a San Francisco drag queen and World War II veteran, also became the first out gay candidate to run for public office in the U.S in 1961. Leonard Matlovich, a former soldier who sued to fight the military’s gay ban, graced the cover of TIME in 1975. “When I was in the military they gave me a medal for killing two men and a discharge for loving one,” his tombstone famously said. Harvey Milk, who settled in San Francisco after serving in the Navy, became the first out gay elected official in California in 1977—though he was assassinated one year later.

By 1984, a New York Times article reported that 40% of single men in San Francisco self-identified as gay. San Francisco still has the highest percentage of LGBT-identifying adults at 6.7%, when compared to other large metropolitan areas, per a 2021 UCLA Williams Institute report. A fall 2022 poll by the San Francisco Standard found the number to be much higher—with 23% of the city’s electorate identifying as LGBTQ+.

“San Francisco remains one of the cities where LGBTQ+ people have claimed the largest place, publicly, in culture, politics, society—where we are an institutionalized and accepted part of the city’s life and culture,” says Koskovich. “At the same time we’re in the United States, and that means that there continues to be LGBTQ+ phobia, attacks on LGBTQ people, and political organizing against us. We remain a community that has to continue struggling for its rights and for its place in society, even in a city like San Francisco.”